The Wooden Nickel is a collection of roughly a handful of recent topics that have caught our attention. Here you’ll find current, open-ended thoughts. We wish to use this piece as a way to think out loud in public rather than formal proclamations or projections.

1. Trades vs Investments

We’ve spent a lot of time on this page arguing that the most prudent way to get the magic of compounding to work in an investor’s favor is to have a mentality of first focusing on the bottom-up of an investment. Too many people quibble over the multiple a stock trades at as if it’s an engineering problem to be solved and less time on understanding the quality of its assets, processes, and people. Anything held for any meaningful length of time is going to be driven far more by the factors of ROIC, capital allocation, and management stewardship, and as a result, make the starting multiple a rounding error.

But finding those specific opportunities can be few and far between or bid up to extreme levels, so having multiple approaches to the market can be a meaningful value add to building out a portfolio, and one of my favorite approaches is to look for business trading at trough multiples on a cyclical trough in earnings with a good amount of embedded optionality. Usually, these businesses are quite mature and don’t have the runway to redeploy capital at high rates on their main lines of business so they probably don’t deserve premium multiples.

Qualcomm last year was one such situation. Its core handset market has been saturated for quite some time, drying up the stock’s compounding ability. While dominant in the modem market, the company has been losing share going back over 10 years, ever since Apple started insourcing the development of their own phone processors. The Covid boom gave Qualcomm a massive upgrade cycle, especially in the high-end portion of the market. Coupled with favorable news for its royalty business with Huawei, the pandemic saw a boom in the company’s profits. But like with every other Covid business boom came the bust, leaving Qualcomm with record inventory on its balance sheet and sales declining 20%. The narrative on the stock provided its own hurdles, eating up mindshare among investors.

- The smartphone market was saturated, lacked long-term growth drivers, and competition was taking share in low-end segments.

- Qualcomm’s largest handset customer, Apple, was well-known to be trying to create its own modem product so as to avoid paying Qualcomm.

- Sanctions against Huawei were cutting off another key customer while China was simultaneously investing in its own chip sector.

Qualcomm’s business has all the trademarks of a legacy moat; its profitability, return metrics, and earnings power derived from prior invested capital. In these types of situations, where the assets have durable qualities but lack incremental returns, “buying cheap and holding dear” is the best course of action. The stock got cut nearly in half from its peak and even fell as the market rebounded more than 30% in the 6 months from the Q3 2022 bottom. The stock stood at a paltry 12x projected fiscal 2024 earnings.

At some point, enough is enough. There were a number of things that could go right or at the very least turn sentiment around:

- Smartphones wouldn’t decline forever. Even with a saturated market, a stock trading at a 9% earnings yield with competitive advantages is a candidate for accretive buybacks that enrich shareholders.

- Past acquisitions could revitalize the competitiveness of their processor business, regaining share within smartphones or perhaps be used as an entry point into other markets.

- Apple could fail to build its modem due to the difficulty of it and cancel its internal project or at least push out its use of internal chips.

- Qualcomm could bring some new innovations to the phone market by integrating various components and outcompeting peers.

- Automotive revenues would continue to grow and become a material part of the business within a few years.

Where I think most value investors tend to fail is relying too much on the cheapness of the multiple to bail them out and do the work of the investment. It’s better to zero in on “cheap” stocks that genuinely have competitive advantages (even if there are others out there that screen cheaper) and list out plausible scenarios that could boost the business. You didn’t need all of them in the case of Qualcomm a year ago and it was easy to see that at 12x estimated earnings (which themselves had been cut all throughout 2022) most of the bad news was priced in.

Figure 1: QCOM Share Price (White), FY 24 Earnings (Blue) and FY 25 Earnings (Orange) Throughout 2022 and 2023

2. Bloodbath in Software

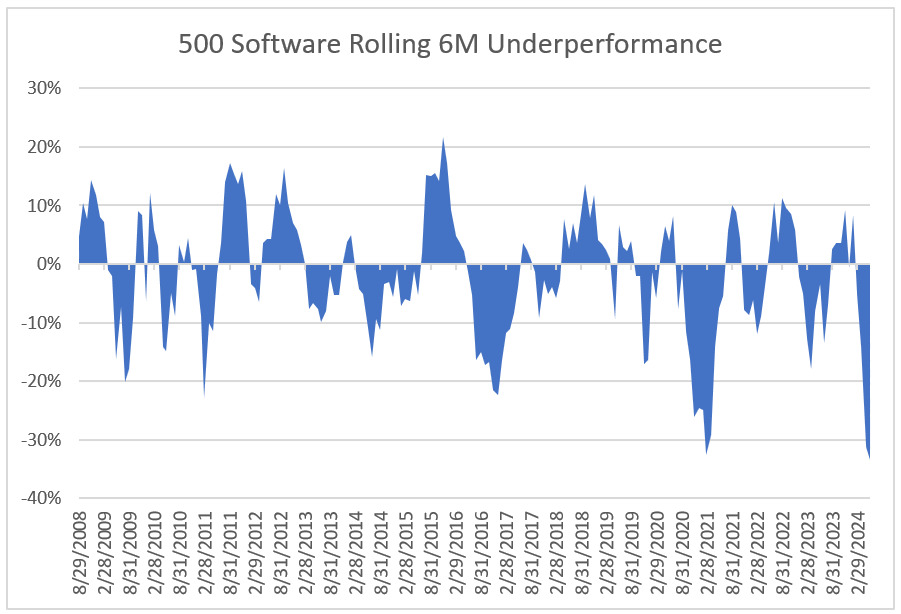

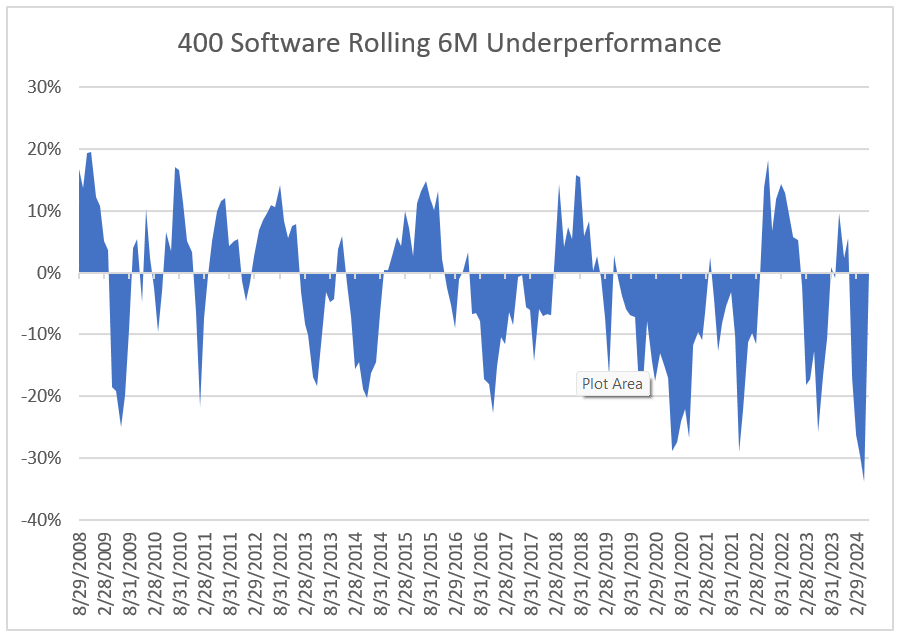

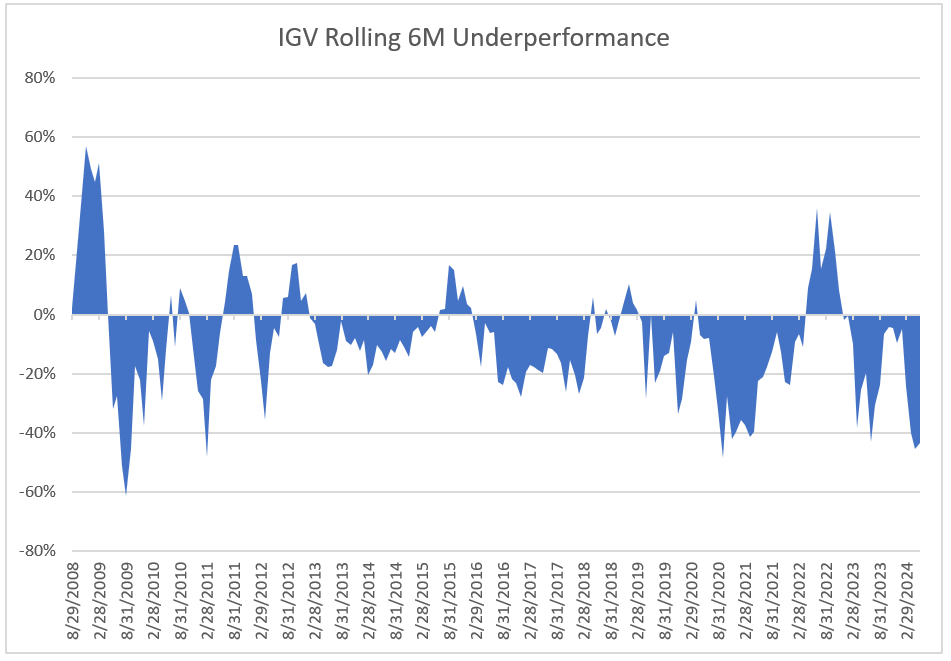

For so long it seemed that any software business that had a subscription story or cloud narrative to sell could do no wrong. Some investors even started saying that a software sale had better credit standing than first lien debt. Yet, the next three charts all tell a different tale (at least in relative performance to the SOXX Semiconductor Index).

No matter what measure you prefer, we’re currently in either the worst software environment ever or merely the worst one since the Global Financial Crisis. While some onlookers are quickly ready to paint some very broad and fatalistic brush strokes, there are several factors at work here:

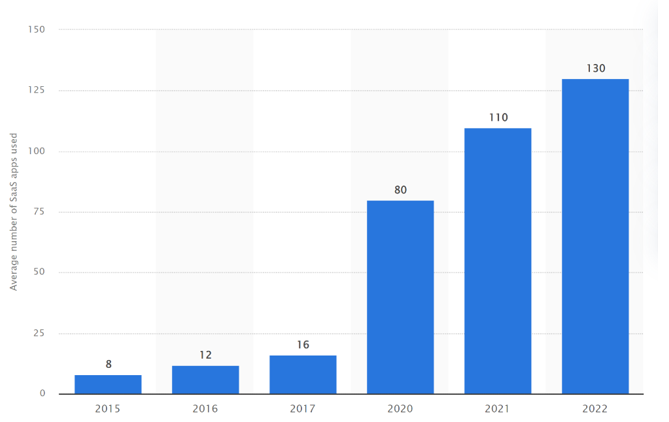

- Software usage has absolutely exploded during and in part, thanks to, the pandemic (Figure 2). The manic buying patterns during Covid gave way to the “rationalization” environment throughout much of 2022 and 2023 where growth rates moderated and software companies pivoted to buckling down on costs and generating cash flow. What looked like an acceleration towards the latter of last year turned out to be a rug pull and instead, I think we’re still digesting the feast brought on by the pandemic.

Figure 2: Average Number of SaaS Applications Used Worldwide, Source; Statista

- Related, the macro backdrop (with an uncertain US and weak global environment) has kept IT budgets in check, limiting the expansion opportunities software companies have.

- Some markets are largely saturated. Customer Relationship Management (CRM) software has been a market of nominal growth as most growth comes from adding on additional products and/or price increases, but for the most part, the CRM market is very developed, as are others.

- Some companies simply weren’t viable from the start either from a strategic concept or an economic structure. We saw plenty of speculative and dubious business types start or emerge during the pandemic only to go belly up. It’s not a surprise that even a great industry like software would have its share of failures or non-viable models.

I don’t think we are in an era of the beginning of the end for software businesses or at least, if we are, the reasons provided don’t register. Yes, AI may make the development of software easier and thus create a greater supply of software companies, but sales/distribution approaches have always been the key differentiator of a well-run software business. Besides, cloud infrastructure resulted in the same exact effect of a booming supply of software companies, but that wasn’t an omen for the industry; in fact, it was quite the opposite. Finally, as a reminder, the performance charts above were relative measures. If we really are entering an era of the death of software then why do we need all those chips? If the latter have value (and I believe they do) it’s because they’re some of the inputs for the applications that we’ll all engage with and utilize.

3. Outsider Capital Allocation

I don’t believe the market as a whole prices in a singular economic environment, outcome, or data point out into the future. Rather, it prices in a range of what’s reasonable or plausible; another reason why consistently outperforming is so hard. Variant perceptions and behavior, where alpha can truly be found, thus must exist a standard deviation or more away from what is consensus, again where the latter is defined in a range rather than a singular point.

Something that’s even more unique than market views is outside-the-box capital allocation. Most capital allocation decisions follow rigid conventions and fail to take advantage of unique opportunities. For instance, share repurchases are often programmatic. Companies dedicate cash flow to buying back stock to try and offset stock-based compensation or are generally agnostic about whether or not buying back stock is a good use of money. So when a CEO makes a decision that is outside the bounds of normalcy, it catches my attention.

Let’s go back to 2022. Both stock and bond markets were seeing significant drawdowns as hot inflation prints pushed up yields, brought on more rate hikes, and of course, created fears of recession. Inventory shortages turned to gluts while growth rates for sales and profits slowed and reversed. Parts of the tech sector were most ravaged, given the pronouncement of shortages that existed (leading to bigger gluts), wasteful spending, and speculative investment in areas such as the Metaverse and crypto.

Perhaps no company personified the pain more than Meta/Facebook. Its share price collapsed 77% from peak to trough, including a one-day 25% decline after an earnings report showing billions of dollars worth of losses in its Reality Labs division.

Obviously, the ship has been righted since then for a number of reasons but a recent disclosure about Zuckerberg’s capital allocation during that tumultuous time stands out. TikTok was growing and rapidly so; it was the fastest growing consumer product in history, at that point in time, and the threat to Meta’s share was real. Launching competing products would be expensive but the glut and billions of dollars worth of write-offs occurring in the chip sector provided an opportunity.

Figure out what you need to compete to the fullest. Then, whatever that amount of resources is, “double it.” That was the instruction Zuckerberg gave. If there was ever a time to be cautious about expenditures it was then, with investors providing vocal pressure. That’s absolutely what most CEOs would have done and understandably so. The economy was believed to be heading towards a nasty recession and there were plenty of other areas to focus on and cut costs. But instead of being a prisoner to the economic context and moment, he sensed a strategic opportunity, did something unconventional, and was absolutely right. Say what you want about Zuckerberg as CEO, or Meta the product/company (I know I have plenty), but from a strategic decision-making standpoint and capital allocation standpoint, he has earned some dues.

4. Recommended Reads and Listens