It’s a striking image: a line of stick-thin metal towers arrayed across oilfields, spewing fireballs that wave like orange flags against the blue sky. The towers, appropriately called flare stacks, burn the gas that is produced during oil extraction in a process called gas flaring. The practice has been done since the beginning of oil production over 160 years ago. Today, there are as many as ten thousand 10,000 of these flames alight at any time, each one a controlled blaze of unwanted gas curling up into the atmosphere.

There are a myriad of reasons that gas is flared. Gas associated with oil production can often be toxic or combustible – flaring the gas can convert these substances into carbon dioxide, a tradeoff that exchanges the potent greenhouse gas, methane, for less-damaging carbon dioxide. Additionally, some gas flaring can reduce pressure in the production equipment, lessening the chance of costly damage or operational disruptions. However, most gas flaring is simply the disposal of natural gas that, for whatever reason, is unwanted.

Gas flaring is widely recognized as a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions as it releases carbon dioxide and carbon dioxide equivalent. Flaring results in around 350 million tons of CO2 equivalent emissions annually, almost one percent of such emissions. It’s also responsible for 40% of black carbon, a fancy name for soot, which accelerates the melting of the Arctic. Even worse, flaring releases benzene into the air, a chemical which can cause serious health issues in local populations, such as respiratory disease, birth defects, strokes, and is a possible carcinogen.

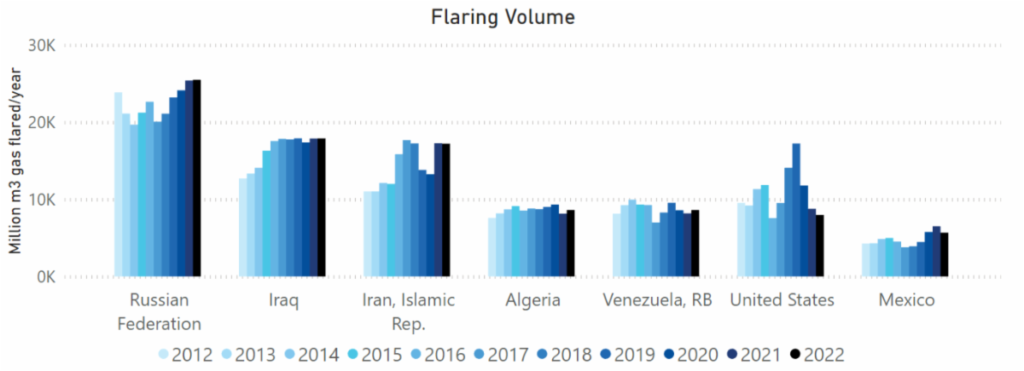

Not only is gas flaring a significant hazard to the public, it’s also tremendously wasteful. Worldwide, approximately 140 billion cubic meters (bcm) of natural gas was flared in 2022 – almost equal to 70% of the natural gas exports from the United States that same year. Ten countries: Russia, Iraq, Iran, the U.S., Venezuela, Algeria, Nigeria, Mexico, Libya, and China make up 70% of global flaring. Estimates suggest that, at the height of the recent energy crunch induced by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, up to $55 billion was wasted due to gas flaring. Russia in particular has been flaring $10 million worth of gas every day at Portovaya, gas that would have been sold in Europe prior to the war.

More often than not, the difficulty of reducing flaring through capturing the gas is the price tag. Capturing and processing the gas into a useable energy source requires the facilities to do so, which are costly in themselves. The locations where oil production occurs are often remote, with little to no existing infrastructure to transport captured gas to market. Additionally, there are regulatory problems that decrease the incentive for oil companies to capture the gas. Permitting issues, flaring fines that are too low, and a lack of oversight and political will all contribute to the issue. It’s been estimated that ending all gas flaring worldwide would cost $100 billion. That’s a hefty price tag for a serious problem.

There are a host of options available to mitigate the harmful effects and incredible waste of this process. On the ground, oil producers could use cheaper, more mobile portable compressed natural gas (CNG) or mini-liquified natural gas (LNG) facilities that could capture and process the gas onsite so that it may be used for production operations, or even trucked elsewhere for sale on commercial markets. Producers could also reinject the gas back into the ground for disposal or storage instead of releasing it into the atmosphere.

At the national level, implementing measures that incentivize capturing and selling the gas – such as higher fines and loosening permitting for capturing and processing the gas – could help decrease the amount that is flared. Governments need to produce clear roadmaps to reduce flaring, which would promote greater cooperation and transparency between the relevant parties. Requiring onsite emission-measuring technology, coupled with the use of satellite atmospheric data, can give insight into both site-specific and regionwide flaring levels. Despite the cost of such measures, it’s likely that by getting the gas to market, they would recoup their own cost in a few years or even sooner. Incredibly, bringing this gas to market could offer relief in tight market conditions by increasing supply by 5-7%, a boost that would be faster than investing in new supply.

There is a moral and economic imperative to ending gas flaring. Certain efforts have been made to reduce it – both the Global Gas Flaring Reduction Partnership and the Zero Routine Flaring by 2030 initiative, both sponsored by the World Bank and other entities, have endeavored to bring together public and private organizations to reduce flaring. Some of the top-flaring countries, such as the U.S., have decreased flaring in recent years, but it has been more than offset by increases in other countries like Mexico, Libya, and China. While the continued widespread practice of flaring is a clear failure of government and corporate ethics, it is not too late to act. Now, more than ever, is the time to mitigate the damage and end such mind-boggling waste.