Investors are getting a front-row seat to Supply Chain 101 during and in the aftermath of the global pandemic. Interconnectedness seems to always be unveiled amid crisis, whether that is financial contagion such as the Asian Financial Crisis or global operations, as is the case currently. The front end of the Covid infected economy reintroduced terms like Just in Time inventory modeling to the regular lexicon. The back end of this cycle is bringing back another term from everyone’s introductory operations classes: the Bullwhip Effect.

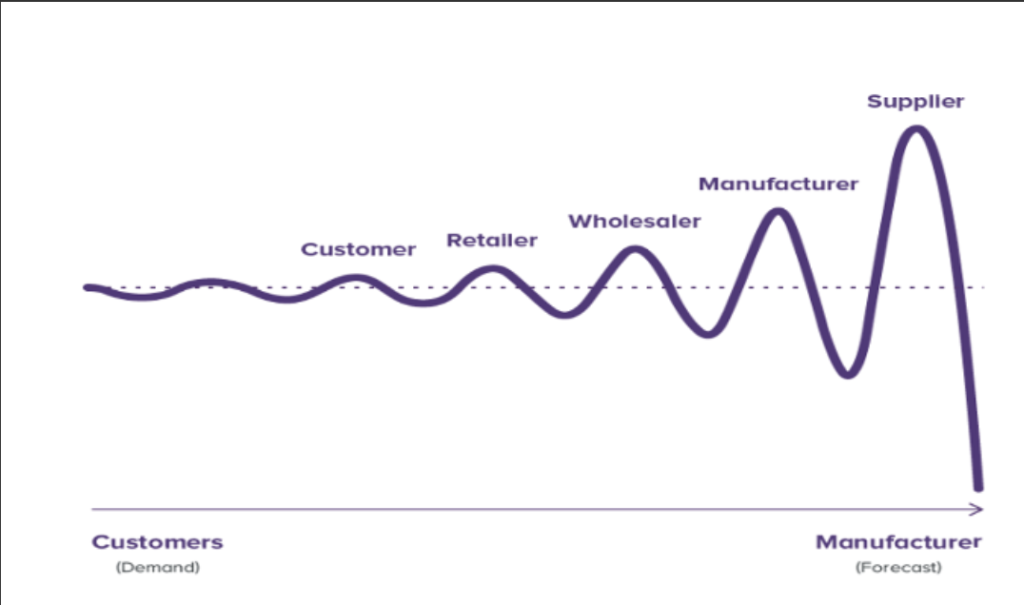

Figure 1: The Bullwhip Effect

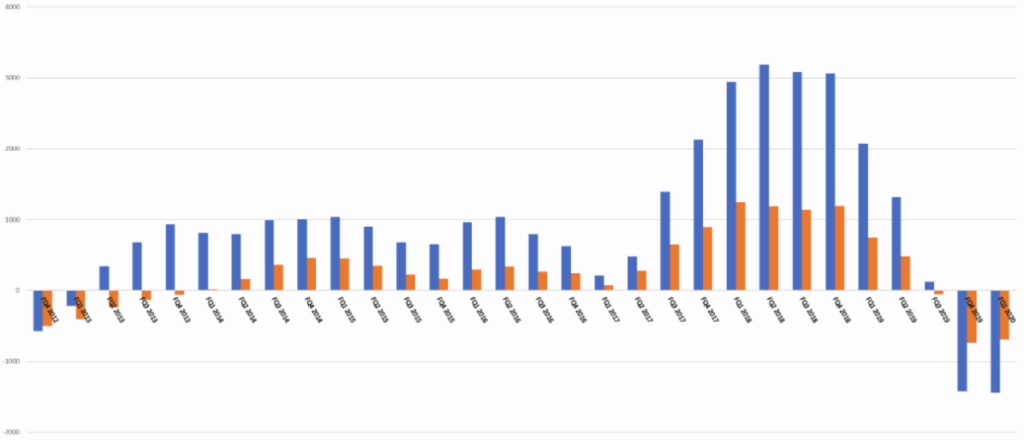

The term describes a phenomenon where a small change at the end user cascades in larger and larger waves each preceding layer. The result is rapid and violent cycles in production at the supplier level. It’s not a new occurrence but usually, the cases are contained to an individual corporation or maybe an industry group. Semiconductors, in the news constantly the last couple of years due to shortages, are prone to it due to their very long supply chains. Changes in demand amplify from users to retailers to brokers, to distributors, to Electronics Manufacturers, to Original Equipment Manufacturers, to fabs, to tools companies, and finally to designers like Nvidia and Qualcomm. The 2018-2019 cycle is emblematic of it (Figure 2). Within a few quarters, the largest upcycle in decades for the industry turned into the worst downcycle since the dot-com bubble.

Figure 2: Lam Research Incremental Sales and Op Income During 2018-2019 Cycle

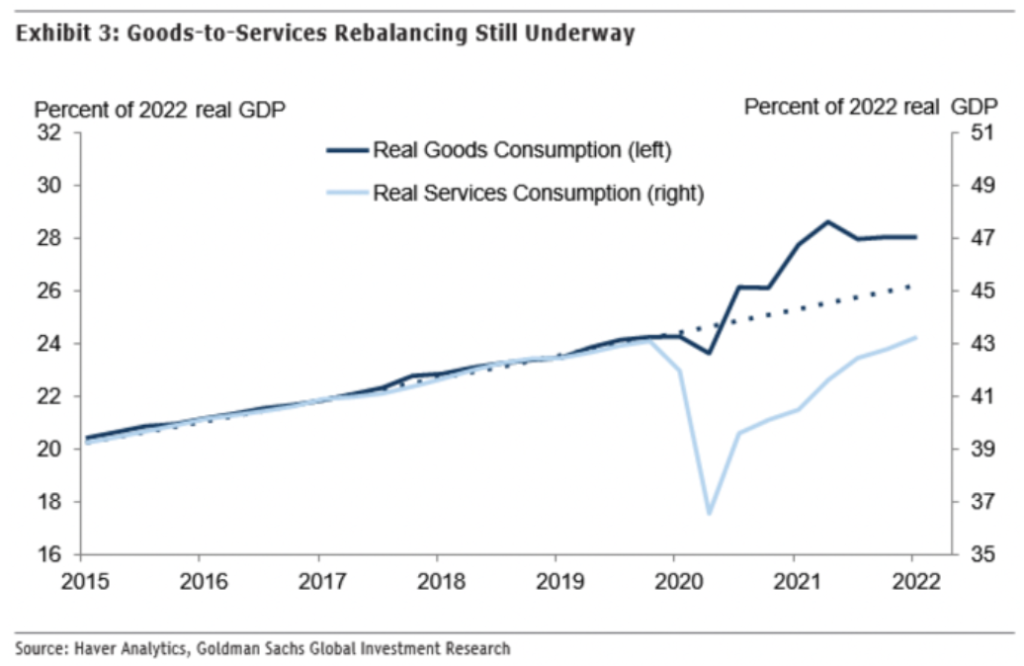

But one of the most significant differences in this market cycle is the scale and breadth of dislocations brought about by the pandemic. The bifurcation between expenditures on goods versus services was historic for understandable reasons (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Consumption on Goods vs Services Needs to Revert, Source: Goldman Sachs

Behavior during severe shortages doesn’t look like the typical upswings of an economic cycle. Order sizes get inflated intentionally, hoping that by being a larger buyer companies get greater attention and priority. A second effect is that companies place the same order with multiple suppliers, spreading their bets on which one will get fulfilled first. They hope product arrives in time to cancel duplicate orders. Finally, other companies, like Peloton, extrapolated demand surges as the new normal, simply overestimating demand.

Data from FreightWaves demonstrates this well by looking at the number of containers per ship (Figure 4). Demand snapped back in 2020 and the ratio between containers (green) and bills of lading (blue) spiked whereas they usually move in tandem. Slowly, demand growth rates normalized. Now, the opposite is happening as order cuts are rolling in furiously.

Figure 4: Bills of Lading vs Containers, FreightWaves

This is a textbook example of the Bullwhip Effect. The difference with some past economic cycles is that we aren’t dealing with small ripples from the consumer but rather some sizeable moves. In the best-case scenario, it’s simply a shift from goods to services with aggregate demand steady. But between things like the demand hangover from Covid, high energy prices, decades-high levels of inflation, the disruption of the Russia-Ukraine war, and China spending most of the spring shut down, the odds quickly shift to demand being destroyed rather than shifted.

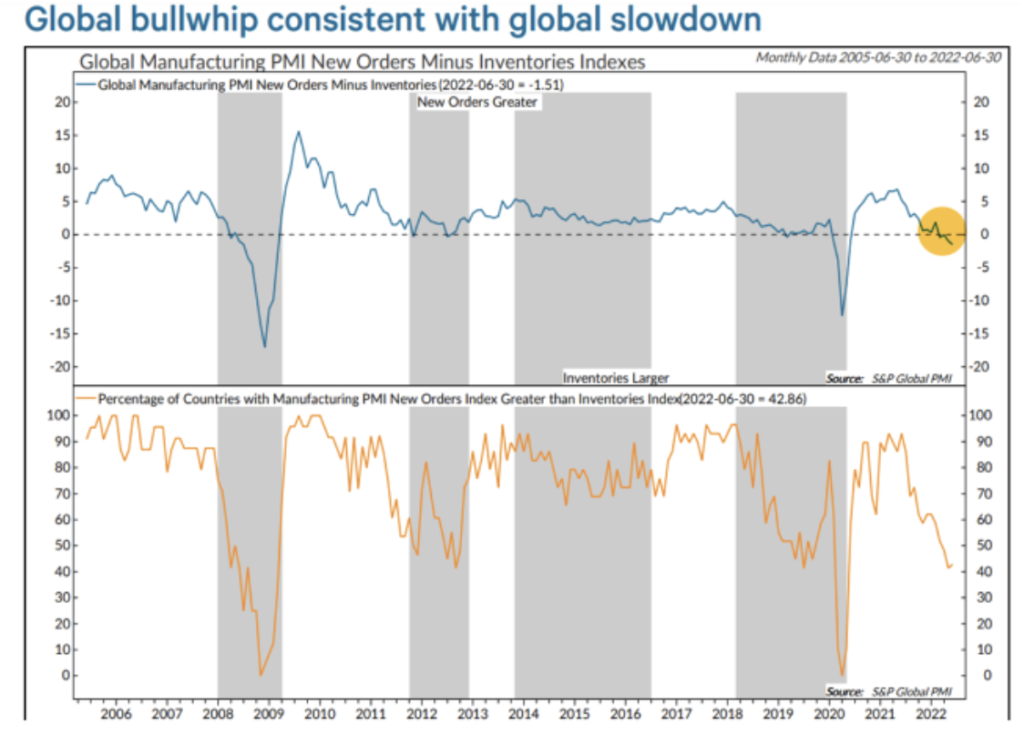

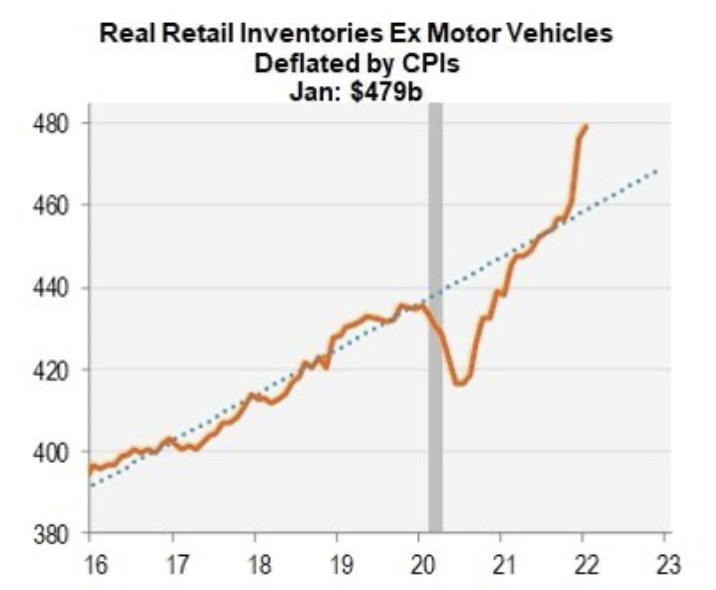

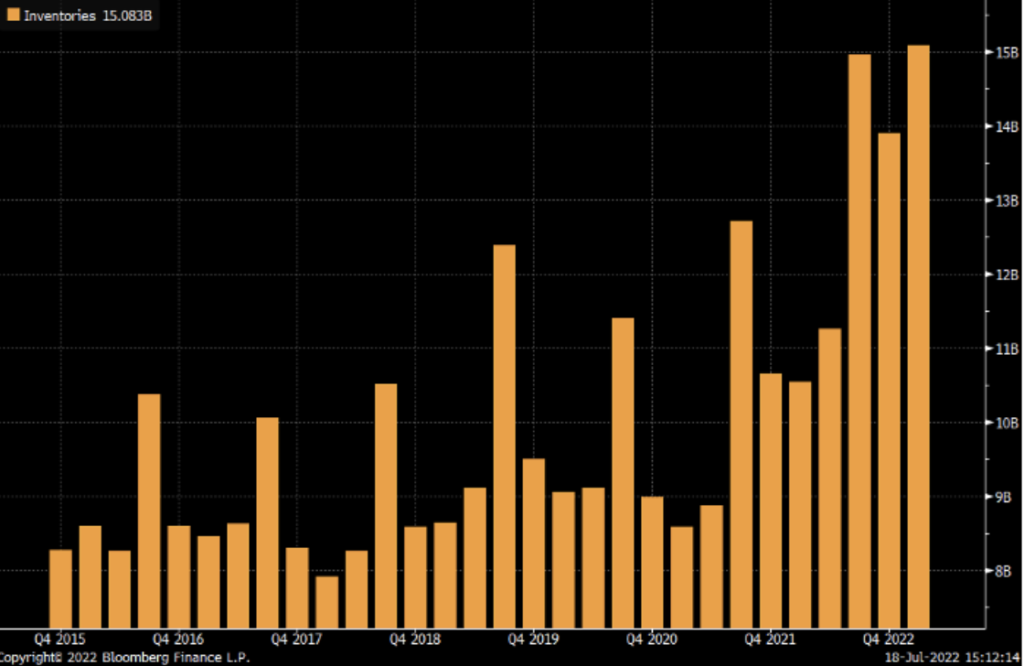

Globally, inventory growth has now surpassed the growth in new orders and there is quite a bit that needs to be worked down until supply and demand can be rightsized (Figure 5). Historically, economic cycles don’t pick back up until excessive inventories get worked back down, restarting the production machine. We have a considerable way to go (Figure 6). Target had more inventory on their books at the end of March than they did in the quarters going into the holidays (Figure 7). How is that sustainable?

Figure 5: Growth in Inventories is Surpassing Order Growth, Source: Ned Davis Research

Figure 6: Can Demand Support This Kind of Inventory Growth? Doubtful, Souce: JP Morgan

Figure 7: Christmastime in March? Target Inventory Higher than Holiday Periods

Target warned inventory would have to be discounted or liquidated to other retailers in order to get it off their balance sheet. The result will be large hits to margins and earnings. How many others will follow?