In the distance, Faust saw something like a flickering orange light. “There must be a fire, out there” he thought, and suddenly Mephistopheles appeared, by stating the obvious: “Yes, of course there is, and it consumes the house of Baucis and Philemon, you know that crooked little house and the ancient trees that obstructed your view, and it was you who asked to be removed.” [i]

Augustus was done with those who were obstructing his views, whether that involved Mark Anthony, Cassius, Brutus, Fulvia, Sextus, Lucius, Cleopatra and her son (son also of Julius Caesar) Caesarion. Now, it was time for praise and succession. Shortly after his return from Alexandria in 29 CE, he sat for days listening to the great poet Virgil who had composed the Georgics. “The time has come to unyoke our steaming horses”, Virgin proclaimed. The battle of Actium was behind him. Anthony and Cleopatra were dead, along with all his enemies. As for Cicero and his annoying voice of speaking truth to power, he was long dead, as Cicero was one of his first victims. Octavian (as he was known before adopting the name of Augustus), at a time when he was practicing the art of war – well before it was explained by Sun Tzu -, had conspired with Mark Anthony in assassinating Cicero in 43 BCE, and consequently ended the era of the Roman Republic.

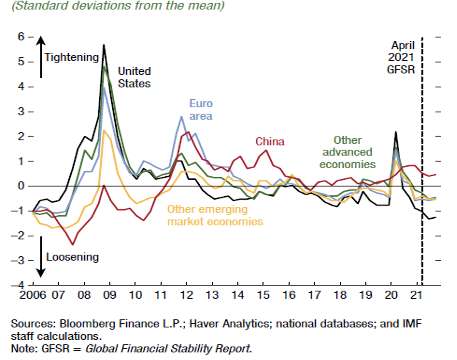

Portfolio managers nowadays look for yields as they try to enhance returns in an era of financial repression marked by zero interest rates. Leveraging assets – a practice taught by Octavian and practiced by Faust – continues producing good results, especially when it involves futures and other derivative products. Experimenting with other alternatives from real estate and private equity, to investing in disruptive technologies and cryptos, could potentially enhance returns, but it certainly also exposes the portfolios to higher risks. Over the course of the next few months, we will be approaching the point of turning not just a page, but rather starting a new chapter, as financial conditions may be tightening (see graph below).

Every new chapter hides surprises, both pleasant but also unpleasant too. We only hope that if it is an entirely bad chapter, it will be a short one in a pretty good book. But what are those elements that could underwrite unpleasant surprises? Let’s try to outline a few of them:

- Economic outlook in the presence of continuing supply chain and price pressures.

- Financial vulnerabilities masked by massive policy stimuli (fiscal and monetary).

- The prolonging of loose financial conditions (which instigated the financial repression) may have been sustaining the recovery, but it could also result in overly stretched asset valuations which could fuel not just financial instability but also economic dislocations (the Great Resignation phenomenon in the US – when more than 4 million people quit their jobs since August – might be one of them).

- Increased risk-taking, while absorbing excess financial liquidity, is also contributing to rising fragilities in nonbank institutions which, in turn, deteriorates the financial and economic landscape. We should understand that the Evergrande case in China is just an example of this risk.

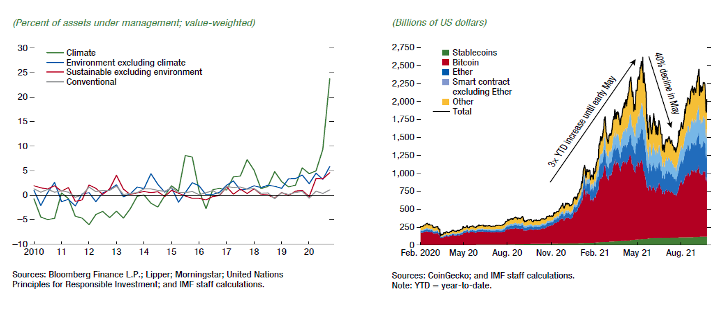

- Aspiration for the Day After, as seen in funds flowing into areas such as climate or cryptos, may create bubbles which, in turn, could undermine financial and economic structures, if an orderly transition is not executed properly.

As we may recall, when Mephistopheles originally appeared as a black poodle, Faust – the forever unsatisfied person and the epitome of a person who is never content – said yes to the chance to reach levels beyond known knowledge, to accumulate wealth, and to obtain power over nature. However, originally Faust refused the traditional Faustian bargain, declaring that he was already in hell. That was the pivotal point: Mephistopheles alters the terms by challenging Faust that if he managed to state that he is satisfied and his tormented spirit wishes to rest, then the Devil will have won. “Done”, Faust declared, and the wager started.

“Done” Octavian also proclaimed in an island near Mutina in the fall of 43 CE, when the opportunity arose to conspire with his enemies (Mark Anthony and Lepidus) and take out annoying voices in Rome, like the one of Cicero. Cicero may have been the one who sided with him and made possible his coronation as successor to Caesar (famous Philippics), but he was expendable. Octavian was navigating, as was Faust when seducing Gretchen and later abandoning her[ii], given that Gretchen – as everything else in Faust’s life – was expendable. Were/are portfolio managers doing the same while sailing the ocean of liquidity driving valuations and cryptos through the roof?

Gretchen is driven into despair once Faust abandons her. Even her brother turned against her, and Faust – like Octavian did a few times to the enemies of his enemies – kills him in a duel. She cannot imagine that her newborn infant baby could live in this cruel world and kills the baby. Gretchen is convicted of murder and imprisoned. Faust appears in the prison and offers to free Gretchen. Gretchen refuses. While forgiving and absolving him, Gretchen refuses to leave her prison. Faust feels that Gretchen helped him to free himself from his diabolical bargain.

Plutarch concluded that Mark Antony was “full of empty flourishes and unsteady efforts of glory.” Mark Antony sought swamps, sank into them, and while in them, got bored. Anthony was seeking a Faustian bargain before Goethe was born. Octavian took excessive risks, and was known for his weaknesses and illnesses just before the battle started, but he also knew – like Faust – how to delegate the battles into Agrippa’s capable hands.

As the new chapter will soon be unfolding, what lessons should portfolio managers learn from Gretchen and Faust’s offer to free her? Would it be better if the portfolios were adjusted in a similar manner that Octavian arranged for the Romans to perceive Anthony as simply non-Roman? After all, Rome could not be governed by a non-Roman. Octavian’s triumph at Actium was just the crown jewel of a Machiavellian pivoting. He was proving himself to be a lion and a fox.

[i] From the second part of Goethe’s Faust, which was published in 1832 – almost twenty-four years after the first part was published in 1808 – and just a few months before his death.

[ii] Gretchen’s seduction is the central point of Faust’s navigations in the first part of Goethe’s story.