By: John E. Charalambakis & Dale Ahearn

Monetary theory, which posits that a change in money supply is the main driver of economic activity, has played a central role in attempts to manage the economy. The three main levers used by the Federal Reserve–the reserve ratio, the discount rate, and open market operations– are frequently used to avoid recessions and control inflation. Recently, however, much attention has been given to a more heterodox approach, referred to generally as Modern Monetary Theory, or MMT. At the heart of MMT, fiscal policy (tax and spending) is irrelevant. Taxes primarily serve the role of wealth and income redistribution (and if inflationary pressures exceed a threshold level, then higher taxes reduce spending and thus inflation). The governments via their central banks have a printing mechanism (governments issue bonds which in turn are bought by their central banks) that renders deficits obsolete. The theory’s implications describe a situation where full employment is sustainable, major programs are fundable through deficit spending – which is the mirror image of the private sector’s surpluses – inflation is muted (due to the fact that we operate in conditions of less than full capacity), interest rates do not rise, and defaults could not be happening because of the omnipresence of elastic money. Do we really need anything else?

While we understand the arguments about money endogeneity (for which there are some valid arguments, but which are best consigned to esoteric discussions among economists), as well as the claim that the governments’ accounting systems are convoluted, given the absence of accurate capital accounts (let alone the fact that government-controlled assets are not properly assessed and recorded in a grand balance sheet), we are also realists. We know that the belief that “free money” will not hit the inflationary frontier is a delusion. Moreover, the threat of coercion that hangs with potential taxation – in order to finance the repayment of debts – is sufficient to reduce the degree of freedom of an enterprise system that desires to promote growth via the engine of increased productivity and of an efficient allocation of resources.

The risk associated with MMT is not just a financial systemic crisis (such as one precipitated by inflationary pressures, currency crisis, and related defaults), but a geopolitical one where the latter serves as the escape clause of a practice/policy applied driven by politics (kicking the can down the road) rather than by scenario analysis. Market systems function best when periodic adjustments are made over time. A system is shocked when it cannot face the consequences of previous actions taken without properly counting the costs.

In the mid-1970s, UK accepted an IMF bailout. Back then, the limited internationalization of financial markets did not result in war, although, geopolitical tensions were substantially elevated. Today globalization increases the chances that a financial crisis will become a linchpin of a blame game.

We will address this problem further in a future commentary. For now, we will briefly consider MMT’s advocacy for zero nominal interest rates. This preference is expressed in central bank policies sometimes called ZIRP and NIRP (zero and negative interest rate policies). Zero nominal interest rates clearly imply negative real interest rates (once inflation is subtracted from the zero rate). These policies have many effects on the economy at large. First of all, they promote a climate of financial repression where savers and retirees are penalized. Second, they amplify risk-taking as yield-seekers accept higher risks for marginally higher returns. Third, they redistribute income from private savers to public debtors. Fourth, as risk-taking is elevated, asset prices rise, but not necessarily in a linear fashion, hence elevating the risks of the creation of an asset bubble. Finally (for this discussion), MMT’s application in China, in the EU, and in the US (in one way or another) since the onset of the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) has contributed to elevating imbalances and inequalities which undermine stability.

It is worth also mentioning that this debt-induced mentality has been running in the bloodstream of corporations for some decades now. Unfortunately, since Modigliani and Miller advocated (M&M theorem) that the form of funding (equity or debt) is irrelevant, corporate creditworthiness has been eroding, corporate debt has been piling up, and crises have become more frequent. Going after “efficient” balance sheets has contributed to the deterioration of resilient corporate balance sheets, and hence, the calls for bailouts at the public’s expense (e.g., GFC, Covid-19), which in turn, undermines the resilience of the economy-at-large and its ability to stand on its own.

Let us now discuss the potential inflationary impact of MMT and the portfolio implications to that for the individual investor. First, we need to reiterate a position that we have been arguing about for more than ten years: Policies that basically add to bank reserves rather than circulate those reserves in the wider economy cannot cause inflation. On the contrary, when the bank reserves become money supply (as it seems to be taking place now), then inflationary pressures become viable.

Inflationary pressures undermine financial stability. Financial instability is the archenemy of portfolios and of real economic growth. As instability settles in, interest rate uncertainty could destabilize the financial landscape, pushing highly indebted corporations and households into cash flow or insolvency crises. The destabilization of rates could undermine exchange rates, which in turn, will mess up both countries’ and corporations’ current accounts and balance sheets, and could significantly affect the value of asset classes, including equities and bonds. Portfolios thrive in conditions of genuine financial stability. Masquerading debt as a tool of prosperity cannot be a wise choice. Our quiver does not carry any more disinflationary arrows like it did in the 1990s and the early 2000s.

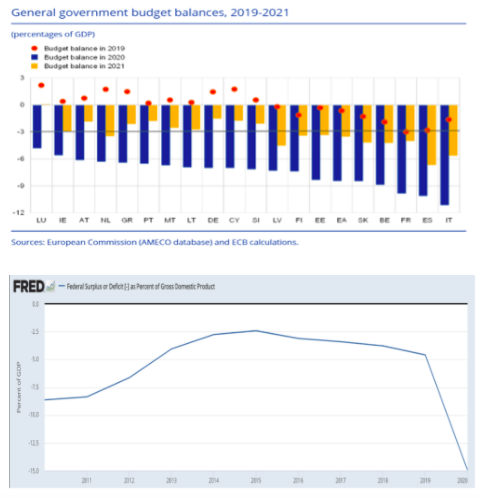

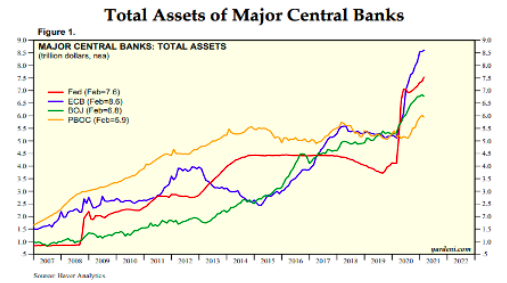

Since the pandemic was declared major economies have collectively increased their deficits by an equivalent of over 20% of GDP. Their respective central banks have collectively increased their balance sheets by the equivalent of 10% of their respective GDP. Some may think that this is, in practice, a partial implementation of MMT. The figures below speak volumes about the dramatic deterioration of public finances in the last year.

It seems that central authorities have started becoming centers of “capital-allocator-in-chief” and central banks’ programs of buying corporate bonds are converting them into back-stoppers of a significant percentage of corporate debt. Simultaneously, we are facing the rising role of shadow banks, and cryptocurrencies are being viewed as an alternative asset class. This whole picture does not pass the stability smell test.

Let’s close this commentary by revisiting a historical conclusion based on facts since the modern era started (16th century). Every time major powers accumulate unsustainable amounts of debt the geopolitical clock reaches an inflection point that energizes the engine of finance. This, in turn, makes the possibility of great-power war more probable.