There is little doubt that the accommodative/expansionary monetary policy of the last 10+ years has been chasing investors and funds out the risk curve but also down the quality ladder. The voracious issuance of corporate debt has been encouraged by a dovish Fed, maybe because we never addressed the cause of the crisis and hence the inability to normalize interest rates around the world.

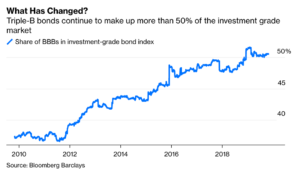

Market appetite for yield begs for more debt, and that in turn compresses spreads and such compression creates the illusion of progress and the delusion of safety. However, the reality is that more than 55% of investment-grade bonds are rated BBB at a time when dealers’ inventory is at the lowest level in the last twenty years, implying an inability to make markets (see figure below).

Monetary policy has lost its cohesiveness and rationality because it lost its moral compass and structure. Paul Volcker’s chairmanship could be characterized as the period of Enlightenment for the Fed. It was the period when the Aristotelian concept of teleology was incorporated into the central bank’s thinking.

The teleological idea implies that monetary policymaking has a proper end in its character and mission, while not isolated from an overall statecraft strategy. The post-Volcker Fed rejected the teleological physics and ethics in monetary policymaking, which ultimately reduced the Fed into an institution expurgated of its central content and converted it into a machine of perpetual asset bubbles.

With such an incomplete framework on which to base the moral understandings of monetary policy- making, the central bankers decision-making process was doomed from the beginning. The arbitrary incoherence practiced by the Fed in the late 1990s and mid 2000s – when they allowed derivatives to grow from a notional value of $50 billion to over $700 trillion – created a pyramid where the moral agent became not the teleological end but rather a cabal of inexplicably subjective set of rules and principles.

This in turn degenerated monetary policymaking into an inadequate framework of thinking where moral emotivism dominates. The result has been that the assumptions and presuppositions that should guide monetary policymaking have been turned on their own head. Here are some examples:

- Monetary rules and targets are supposed to be based on virtues which in turn are derived from an understanding of the telos (end). The post-Volcker Fed has reversed this and predicated virtues on an understanding of subjective principles and rules without any consideration of the teleological implications.

- Aristotle’s assertion that virtue and morality of policymaking are integral parts of an institutional body that has a clear social and not personal understanding of the telos, has no place in the post-Volcker Fed.

- The moral authority of the Fed has been lost because a Nietzschean mentality has prevailed where a subjective set of rules has become the arbitrager of moral questions related to policymaking.

- In a classic Nietzschean framework of analysis, the post-Volcker Fed has been creating fictions built upon myths of a great superstructure, empty of shared standards or virtues which only can be found outside of that superstructure, i.e. in the transcendent.

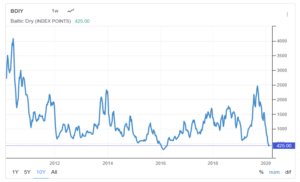

As we contemplate the above in the midst of the coronavirus, we are also wondering as to what the bottoming of the Baltic Dry Index might mean for the economic cycle under formation. How in the world did the index fall from almost 2500 last September to the lows of 425 last Friday?

Of course, when Nietzsche replaces Aristotle, everything is possible…