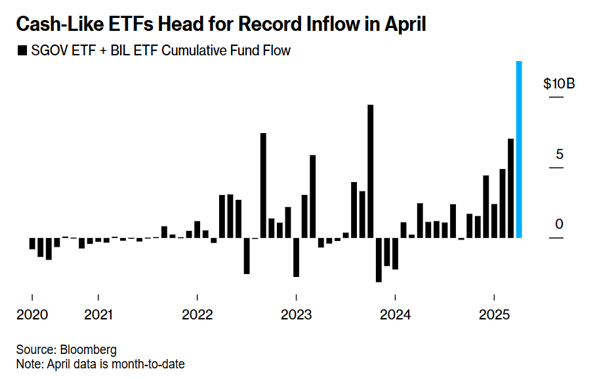

When a market (or any institution) lacks an anchor, a myriad of negative repercussions unfold, starting with the lack of tranquility. The absence of the latter creates uncertainty, and the effect of the uncertainty is turmoil. In the following graph, we see the impact of turmoil in the markets: Investors pull their funds from equities and bonds and park the funds in money markets.

For more than three months now, the focus of our commentaries (as well as of our other publications) has been the rising market turmoil, whose epicenter is the role that the dollar plays around the world (see e.g. here, here, and here).

In Volume II and Book IX of Seneca’s Moral Essays, we find an outstanding piece/dialogue between Serenus and Seneca about tranquility: “In truth Serenus, …what you desire is something great and supreme…to be unshaken…what we are seeking, therefore, is how the mind may always pursue a steady and favorable course, may be well-disposed towards itself, and may view its condition with joy, and suffer no interruption of this joy, but may abide in a peaceful state…this will be tranquility.”

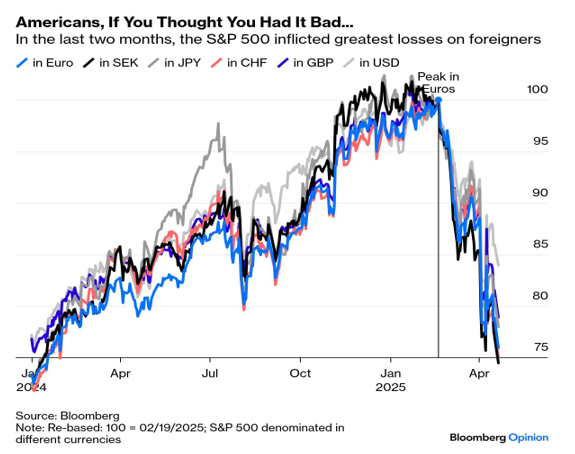

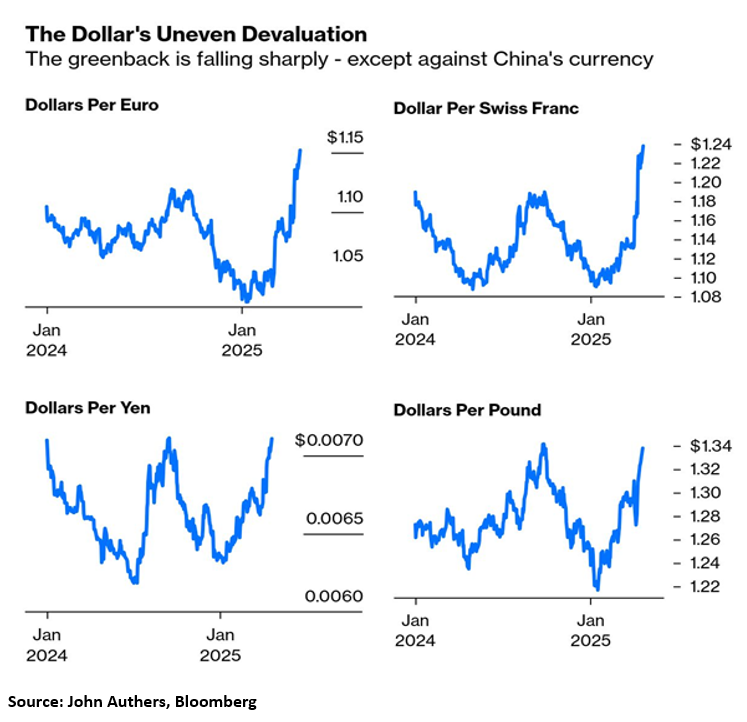

Now, let’s ask ourselves: What kind of tranquility could foreign investors in US assets enjoy given the following graph, which shows that foreign capital has suffered much more than the US investors, and consequently, they may be parking their capital in money markets (see graph above) until they decide what to do with it? A pullout from US markets could have a number of negative ramifications, especially when we consider that trillions of dollars have flooded the US markets in the last 15 years. Let’s not forget that the 1970s turmoil had its roots in the late 1960s when foreigners started pooling their gold reserves from the US because they could no longer trust the dollar and its relationship to gold.

The equivalent law of gravity in economics and finance deals with the anchor of the markets, i.e., the dollar (which replaced the role of gold as an anchor at the Bretton Woods Conference in July 1944). When turmoil/instability starts in the dollar and, consequently, in issues related to the role it plays in global finance, then a snowball of negative reactions starts (in both equity and debt markets) that has the potential of outturning the tranquility that the anchor produces. The world tasted that earthquake in the early 1970s that produced a lost decade until Paul Volcker brought back stability by strengthening the dollar and refusing to applaud the Plaza Accord (September 1985) that cheapened the dollar.

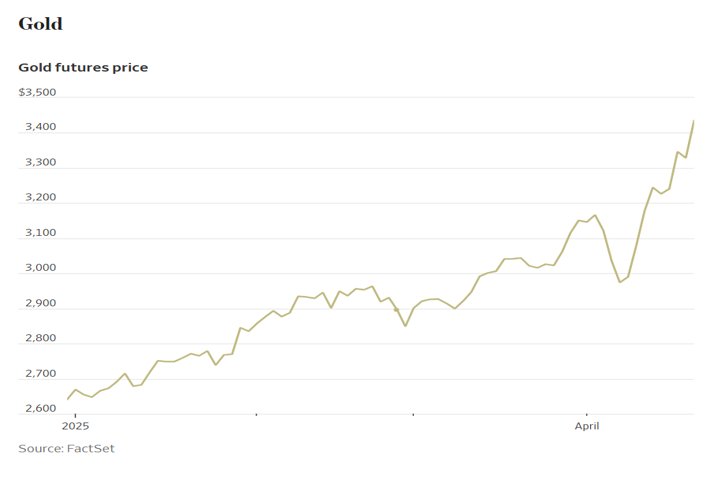

What would have been the result then, if someone’s portfolio had a good proxy/anchor such as gold during the recent turmoil? In one word: Tranquility.

Tranquility is the outcome of policies that avoid arrivistic manipulations, which most – if not all – of the time result in disasters, like in Japan in the 1980s. The Japanese miracle of the 1960s and 1970s was the result of US assistance, technology, export-led growth, and geopolitical diplomacy given Japan’s location next to major Cold War adversaries. What followed the Plaza Accord was financial engineering, deregulation, foreign capital inflows (which flooded Japanese markets expecting gains from currency appreciation), and a very loose monetary policy that included (among others) significant increases and boosts in credit extension. The monetary expansion brought in low interest rates that boosted investments in all sectors, but primarily in real estate (between 1985 and 1987, land prices increased by 44%) and stocks. Corporations discovered that they were making more money in real estate and stocks than in their own operations and consequently shifted their investments from their core business into speculative moves related to real estate and stocks.

Welcome to the snowball effect, where leverage reigns supreme (due to low rates) and a bubble is feeding itself. By 1990, land in Tokyo cost 40 times as much as comparable land in London, making Japanese land worth $20 trillion, which was roughly five times the value of all land in the US!

The appropriation of tranquility is also important. Let’s listen to Seneca: “Let us seek in a general way how it may be obtained; then from the universal remedy you will appropriate as much as you like. Meanwhile we must drag forth into the light the whole of the infirmity, and each one then recognize his own share of it; at the same time you will understand how much less trouble you have with your self-depreciation than those who, fettered to some showy declaration and struggling beneath the burden of some grand title, are held more by shame than by desire to the pretense they are making.”

When I read the above lines, I am thinking: “Wow, is he writing for those who lived at the time of the writing around 63 AD, or for the generation which has been experiencing turmoil since we decided to jeopardize the role of the financial anchors?”

The arrivistic manipulations in Japan included opaque arrangements among corporations and banks that encouraged speculation and contempt for fundamental measures, to the point where tokkin funds exploded from ¥2 trillion to over ¥30 trillion in just four years! Regulations allowed the replacement of safe collateral assets with equities, making the whole system more vulnerable and more shaky. The Japanese equity market was experiencing years of “exceptionalism” with gains close to 400% in just seven years! It took more than 10 years for the Japanese equity bubble to burst (it started bursting in the early 1990s), and by the time the bottom was reached (2002), it had lost 78% of its value, while real estate prices bottomed in 2005, having lost 76% of their value.

The above might serve as a warning that it may not always be wise to buy the dip. When markets are going through political cycles, a disaster is in the works. The Japanese markets’ bubbles were political creations (lower rates due to political arrivistic games, overextension of credit, currency out of sync with market forces, speculative fuels that drove valuations into irrational ranges, etc.). The Japanese experience could be characterized as a silent depression, even though during the years when the bubbles were bursting, recessions were not deep and lasted on average about one year. However, the Japanese economy had lost the confidence game, especially as scandals started revealing the depth of the corruption.

As I was about to board a plane, I saw from a distance Seneca and Volcker. Seneca was holding a poster, which stated the following: “Those who are plagued with fickleness are those who lack mental poise…such men are always unstable and changeable…”, and Volcker’s poster had four graphs:

Why wasn’t Volker standing and applauding (as everyone did) the cheapening of the dollar during the Plaza Accord celebrations?