The Wooden Nickel is a collection of roughly a handful of recent topics that have caught our attention. Here you’ll find current, open-ended thoughts. We wish to use this piece as a way to think out loud in public rather than formal proclamations or projections.

1. Puzzles and Mysteries

There once was a man who left his local watering hole having drunk far too much. Fortunately, he lived nearby and proceeded to walk home. Reaching his front door, he realized his keys were gone, missing from his coat pockets. He began retracing his steps back to the bar. He stopped at a light post when a friend approached him, “Is this where you lost your keys?” the friend asked. “No,” replied the drunk, “But the light is better here.” Just because something can be done doesn’t mean it must be done.

It’s often said, jokingly, that economists have “physics envy.” The attempt to model and map human behavior does not follow real “laws” like those of physics, and so economic models work until they don’t, unlike those employed and developed by Newton, Einstein, and Feynman. If it’s true about economists, it’s doubly true of investors and market strategists.

Mervyn King, in his book Radical Uncertainty, describes how people are often faced with one of two kinds of problems: mysteries and puzzles. Puzzles, like the world of physics, follow immutable laws. The world of puzzles is fixed. It is stationary. It is constant. The pieces fit where they fit every time, over and over again. As a result, it can be engineered. It can be optimized. Mysteries, on the other hand, possess inherent limits to the degree they can be understood. Mysteries possess an unquantifiable number of dimensions. Modeling them requires making assumptions and putting an amorphous blob into the parameters of a square. For some, the uncertainty invites humility. For others, hubris.

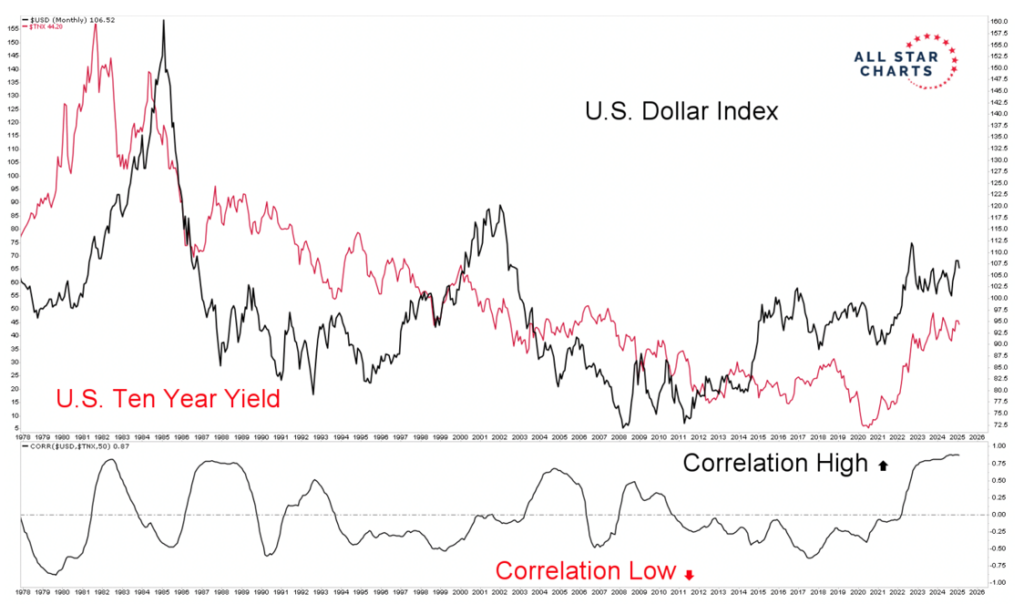

Correlations are embedded deeply into investment truisms. If you zoom in enough on a narrow enough timeline and with a limited set of actors, those correlations can be strong: strong enough to imply linear causality. But it’s all an illusion of myopia, for outside the field of vision are pieces and factors beyond one’s control that have shifted ever so subtly to create an entire new picture.

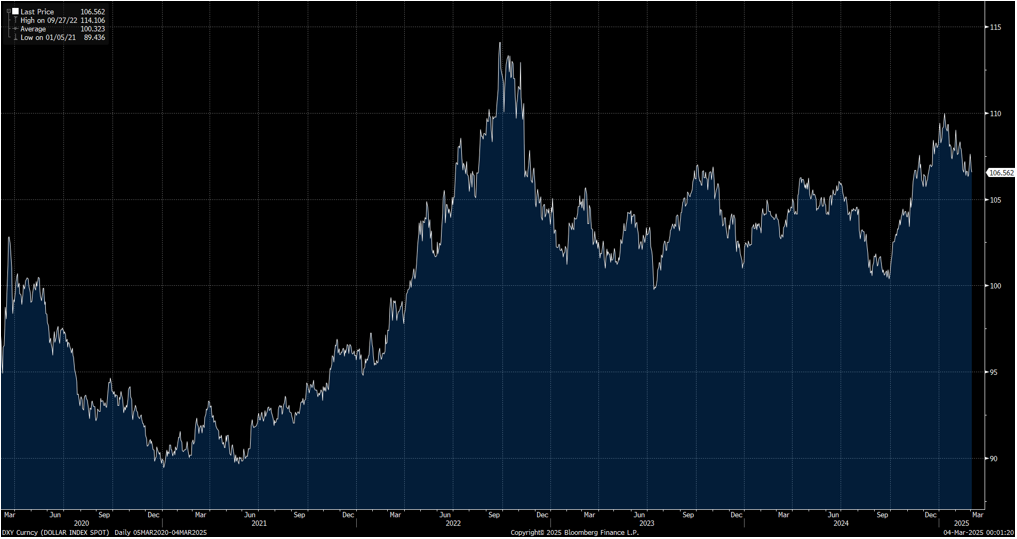

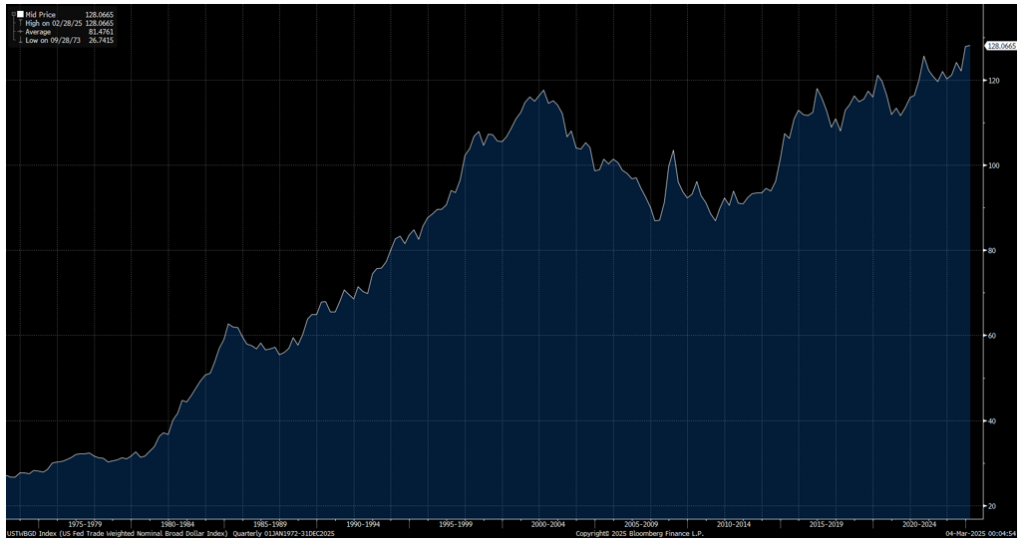

Take interest rates and the dollar in our post-COVID world. With the worst inflation in more than a generation, the dollar has moved to elevated levels on the back of an aggressive hiking cycle that attracted even more capital into the US. Rate cuts have given some of that back. Or have they? The commonly cited DXY Index is elevated, implying a strong dollar but off its 2022 highs. But in trade-weighted terms, the dollar has literally never been stronger. In fact, for the latter, the only noticeable period of decline (in the mid-2000s) came amidst both a) a cycle of rising interest rates and b) growing trade deficits.

Figure 1: The DXY While Strong Has Given Up Gains

Figure 2: The Trade Weighted Dollar is at All Time Highs

Better yet, let’s zoom out a bit. When trying to forecast the ramifications of a policy shift on the dollar or long-term interest rates, what world are we pretending to live in? The world of the 1980s and early 1990s where a falling dollar coincided with bond bull market? Or are we back to the conundrum where long-term rates stay still or rise while capital flows out of the country and to the rest of the world, as was the case leading up to the Global Financial Crisis?

Figure 3: Correlations Are Not Constant. Neither is the World

So when I hear certain policy makers boast with confidence that 10% across the board tariffs won’t do damage because a 4% increase in the currency will offset it, I must admit that I scratch my head. What happens at 3%? Are we in hyperinflation? At 5% are we in a depression? Is the mystery really gone and solved? Is the world the same then as it is now?

Munger once said that envy was the stupidest of all sins because it was the one you couldn’t have any fun with. Investors losing themselves over the relationships of the past regime will surely not be having fun if we are indeed in the early stages of a Bretton Woods realignment. Mysteries should be embraced, not engineered.

2. A Growth Scare?

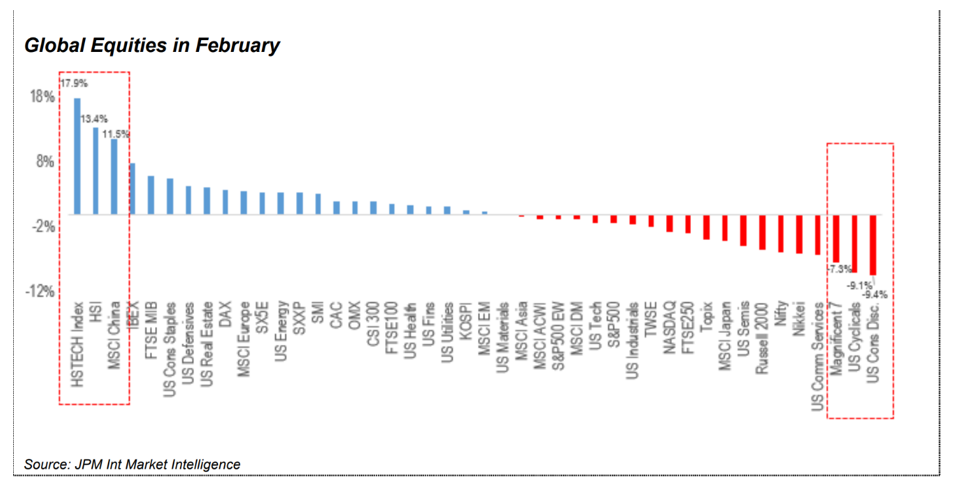

If I told you that stocks would be flat from the day before the inauguration until today, putting us within 3% of all-time highs on the world’s leading equity index, that the financials sector would be at all-time highs, that European markets and China would rip to the upside to kick off 2025, you probably wouldn’t think there’d be a slew of articles speculating on a growth scare in the economy (see here, here, and here just for a few quick examples) and yet here we are.

On the margin, fragile cracks in the economy on a fundamental level are showing up. They’re not an omen per se; there is almost always some part of the economy that lags others. But as they say, trees don’t grow to the sky. Trends don’t last forever. And oftentimes the positives that outweigh the negatives lose steam before the laggards can catch up.

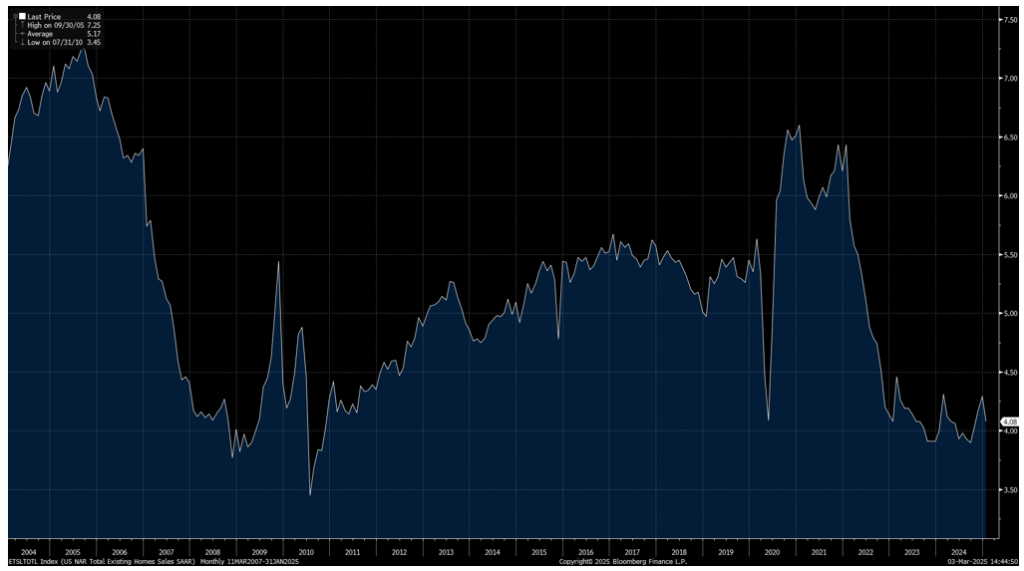

Take housing: An aggressive hiking cycle has taken housing to the woodshed but there was enough momentum in other parts of the economy (wage-led income gains, fiscal spending, capital investment, etc.) to sustain. But as the latter wanes, the weaknesses in the former come to bear. Existing Home Sales have sustained at GFC levels for the better part of two years. New Home Sales could fill some demand for the few buyers out there and do so profitably, given the lack of competition, but again, no trend lasts forever.

Figure 4: Existing Home Sales at GFC Levels

Similar patterns are available in the labor market. The biggest laggards in hiring during the COVID pandemic (leisure and hospitality, healthcare, government) came roaring back and powered the majority of the gains in recent quarters. But this, too, can only run so far. Fiscal spending supplemented state budgets coming out of the pandemic, but that has slowed per Renaissance Macro. State spending grew over 19% in 2023. That slowed to 4% in 2024.

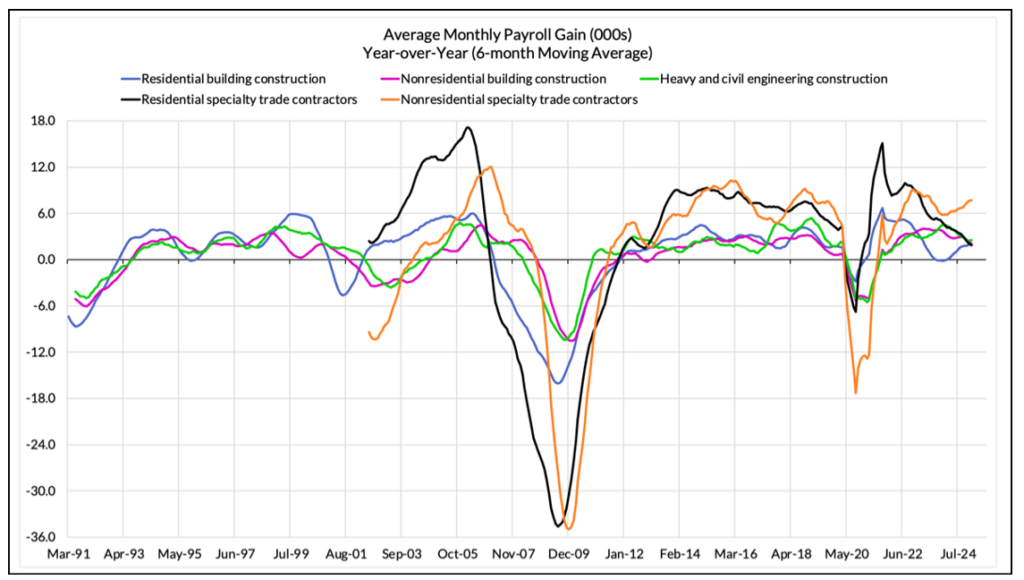

Construction employment has also started to peter out, held up more and more by “nonresidential specialty trade contractors,” aka data centers. And this is all before the impacts of tariffs on building materials are felt and before immigration clampdowns impact labor availability.

Figure 5: Data Centers are Holding Up the Construction Labor Market, Source: Employ America

These macro fundamentals have been slowly crystallizing for a few months but in the meantime, crowding in the markets and bullish enthusiasm has made positioning lopsided. You don’t need a bad economy to capsize herding behavior.

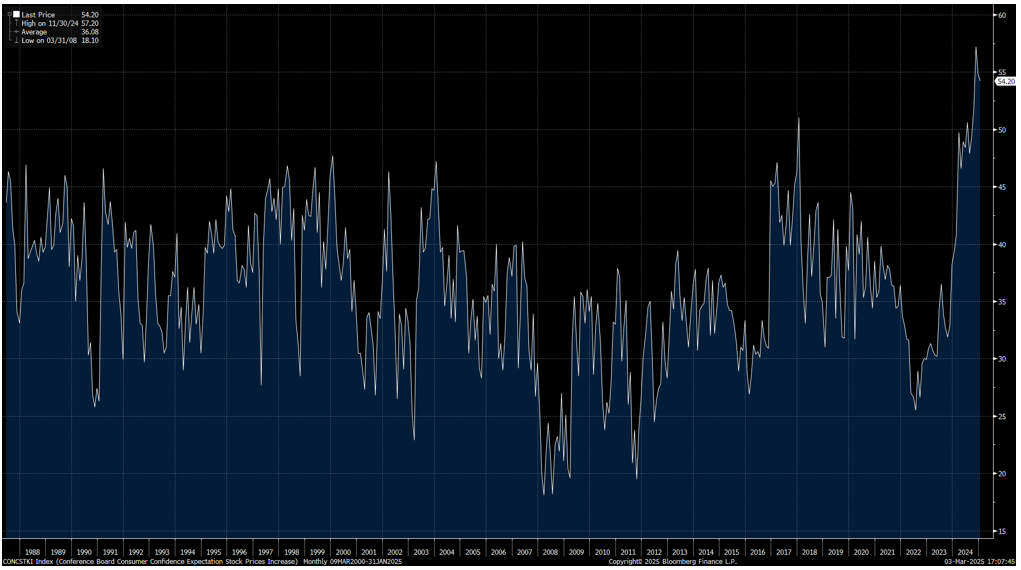

Consider this: even before the election and the alleged dreams and promises of “the most pro-business administration”, every day consumers were more ebullient about the future of the stock market than ever before. According to the Conference Board’s monthly survey (which produces key economic indicators like the LEI), 56.4% of consumers expected higher stock prices over the next 12 months based on the survey conducted in October. It may not sound like much, but that level was the highest recorded point in the history of the survey going back to 1987. Higher than the dot-com bubble. Higher than the credit bubble of the mid-2000s. Higher than the COVID bubble. And that figure kept increasing in the months that followed.

Figure 6: Record Levels of Consumer Bullishness on Stocks, Source: Conference Board

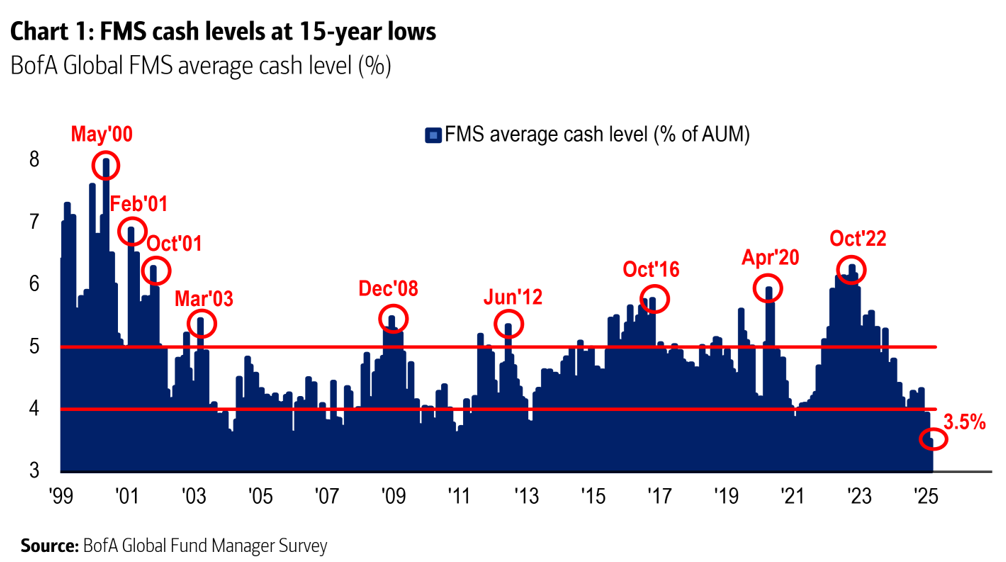

That bullishness sent cash levels down to their lowest point in 15 years according to Bank of America, on similar levels or worse than the bear market of 2022 and the years leading into the GFC. For all the hollow rhetoric about investor sentiment turning negative recently it is always better to watch what they do rather than what they say.

Figure 7: Investors Are at Record Bullishness, Source: Bank of America

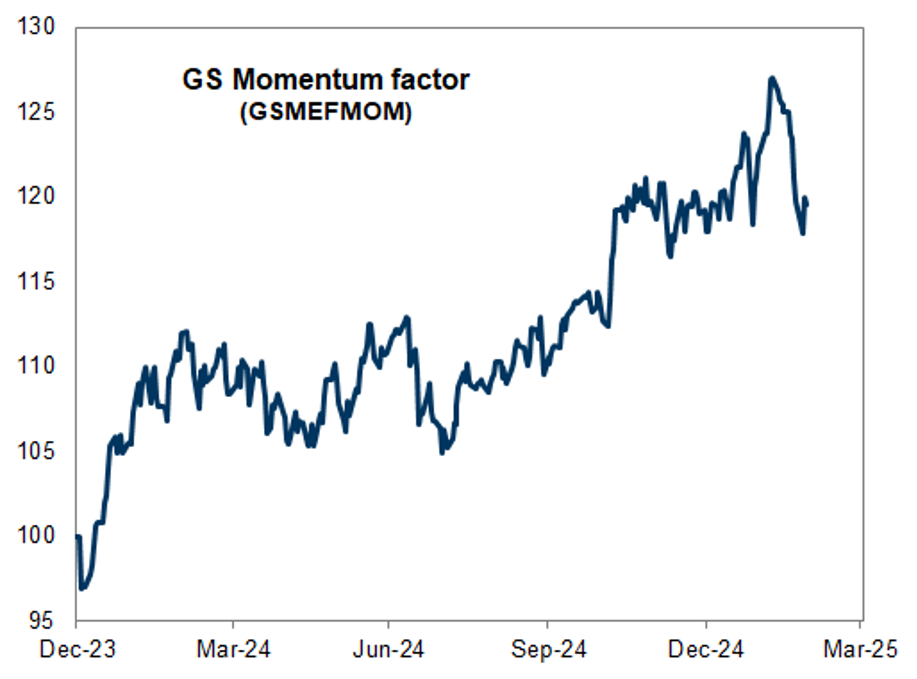

And what did they do while drawing down that cash? They pumped it into what they knew had been winning. The Magnificent 7, crypto, AI and anything else that had a specter of shine to it. The surge reflected a circular logic: buy the winners because they were winners. And then the tide went out in February. If you’re going to be a sheep and move with the herd don’t be surprised if you get culled.

Figure 8: Goldman’s Momentum Basket Surged to End 2024…Leading to a Correction in 2025

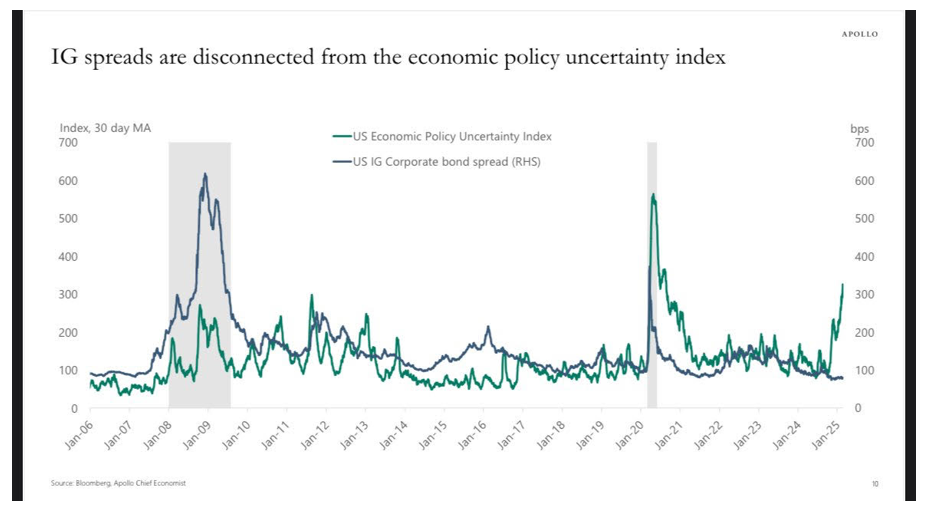

For now, the most telling evidence that the balance of risks lay more in market dynamics (for now) and positioning versus macroeconomic comes from the bond market where borrowing spreads remain lifeless (though expensive). They imply a slowing of growth rather than something more calamitous, but emphasis must be laid on for now.

Figure 9: Business Fear Has Not Translated to Borrowing Fears, Source: Apollo

3. Recommended Reads and Listens