The Wooden Nickel is a collection of roughly a handful of recenttopics that have caught our attention. Here you’ll find current, open-ended thoughts. We wish to use this piece as a way to think out loud in public rather than formal proclamations or projections.

1. Another False Start for China?

In the beloved Peanuts comic strip, one of the most popular skits involves Lucy’s annual promise to hold a football for Charlie Brown to kick, only for her to pull the ball as Charlie gets ready to strike, sending him on his back in a painful landing. Year after year, Lucy charms Charlie into thinking the games are in the past and today is a fresh start, yet without fail Charlie ends up in the same spot time after time: on his back, belly up.

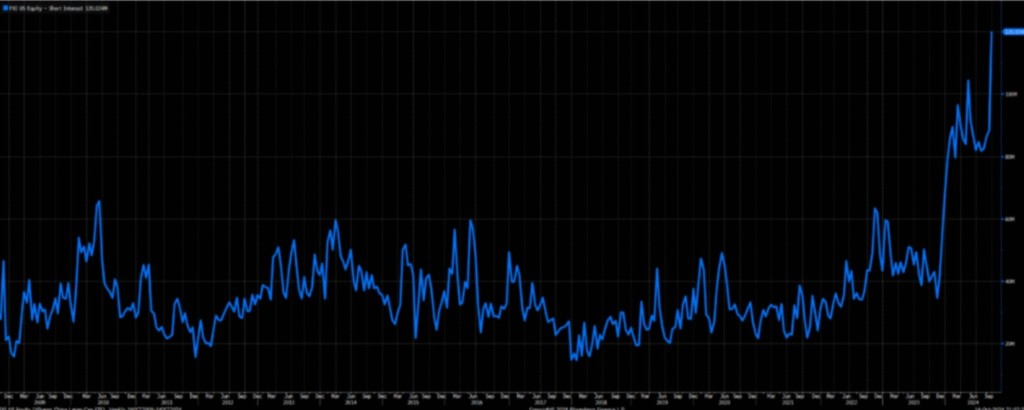

China has held the metaphorical football quite a few times for investors in the last several years. Many still cling to China’s galvanized response to the GFC as an example of the country’s ability to rise to a challenge. And there have been plenty of challenges more recently and from a multitude of areas from Covid to demographics, and of course debt burdens. The Party’s allergy to individual wealth creation led to crackdowns on wealth and industry, leaving fewer people believing in economic mobility. Economic growth has been meager even if you believe the official data. But each attempt to jumpstart the Chinese economy has been futile, akin to pushing on a string. That’s how you end up in a situation where Short Interest in large-cap Chinese stocks hit new post-GFC highs earlier this year, and also how a company like JD can be so cheap that over half of its market cap sits in cash on the balance sheet.

Figure 1: Record Short Interest in Chinese Large Caps

Chatter has once again gripped markets in the past month and China wants out of this economic malaise. Officials from economic authorities and the Party have made dramatic statements about coming support and signaling that it doesn’t want to stand in opposition to capital markets and wealth generation, even guaranteeing loans to buy stock for domestic citizens. The combo of short positioning and official statements has set a fire underneath Chinese stocks with the KWEB Internet ETF up 50% in a week. The potential has captivated some of the world’s best investors. Is this time truly different?

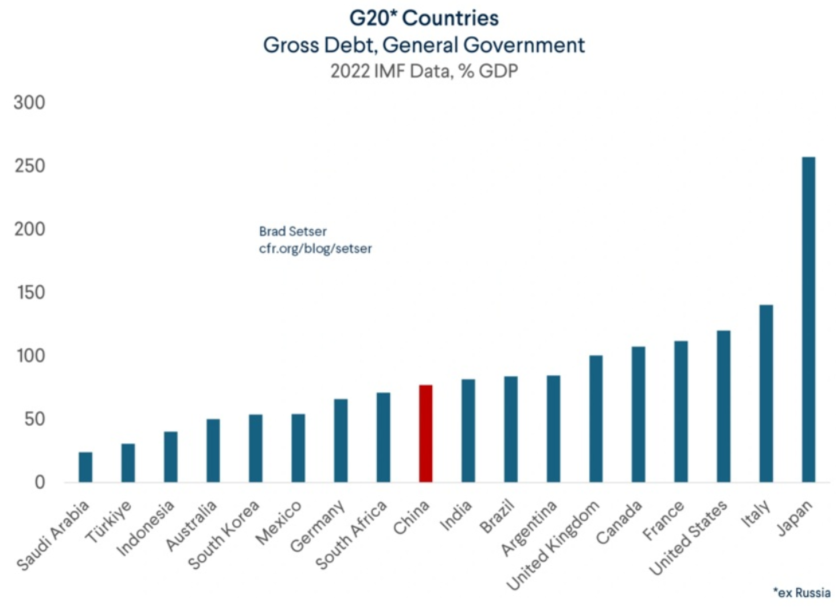

From where we sit today, it seems too soon to tell. But there are traces of whispers suggesting that it’s not the same old, same old in China. For one, and as US investors should be able to sympathize with, when monetary means have been utilized and exhausted and still don’t spark demand then continuing to use them is akin to pushing on a string. Debt swaps, interest rate cuts, and reserve ratio reductions have all been used extensively in China to no avail. What good are further supply-side and monetarist stimuli when you’ve used them repeatedly and pushed your money supply to be twice the size of the US economy with GDP 10% smaller? These measures can only go so far in sparking demand. But now China is openly discussing using fiscal measures to boost consumption and there is plenty of fiscal room in China, even if you account for the debt of provinces.

Figure 2: China Has Plenty of Fiscal Capacity, Source: Brad Setser, Council on Foreign Relations

What those fiscal measures could be is still unknown. If it’s a simple debt swap between central and provincial authorities to free up capacity at the latter, then the fruits will be limited. If it subsidizes a consumer class that has felt despair for years then we may be on to something, at least for the short term. Reforms within capital markets and private wealth are possible as well and Party leaders seem to realize that economic and technological independence is a road that will require incentivizing wealth creation along the way.

Of course, if they want to be serious about long-lasting changes that can last for generations, then the scope of the conversation involves much more than just fiscal transfers. China’s repression of the household sector has been decades in the making, and its entire set of institutions revolved around it. For that, China will need to surrender the model they have used thus far, which is a much more difficult proposition.

2. Shades of 2014 for Oil?

The oil markets are a funny thing, and I’m not just referring to their current iteration. They attract a lot of attention and where there is a lot of attention there is usually a lot of money to follow. The market is extremely rich in data. Everything from production amounts to rig counts, to inventory levels, and of course, pricing of the commodity itself and its byproducts are all easily available to traders and investors alike. That level of transparency is unique but a defining feature of commodity markets. And it tempts people into having a lot of certainty about both what will happen and its meaning.

Oil markets have mostly decoupled from other markets in the last couple of months; while equities have made new all-time highs and other commodities have gained, oil has been stuck in the $60 range, save for Middle East headlines. They’ve traded on their own set of narratives, namely on fears of a supply glut and even whispers of weak demand. Weakness in markets lends itself to hatred; oil is more hated now than ever before according to Bloomberg. Recent news that Saudi Arabia was abandoning their desire for $100 oil in the name of market share is one such example of recent downward pressure.

Figure 3: Record Shorting in Crude Oil

The combination of relative price weakness in crude and headlines out of Saudi Arabia has some investors harkening back to the fall of 2014. Back then, industrial weakness and peak production from American frackers led to supply builds. Oil prices mimicked the old quote about how one goes bankrupt, at first gradually and then suddenly. In the late summer and early fall of 2014, prices fell 30% from just over $100 per barrel to the mid $70 range. At annual OPEC meetings in November of that year, the Kingdom refused to cut production levels. Oil tumbled an additional 40% in the last five weeks of that year.

Could a replay of those events happen again, given recent headlines? I suppose it’s possible, but I wouldn’t bet on it. Saudi Arabia’s intended audience is different today than ten years ago. Back then, the kingdom was watching its grip and influence over global crude markets erode as shale oil production surged, adding 4 million barrels to an already elastic market. Saudi Arabia was determined to use its production might to try and wipe out Western competitors by flushing them out with lower prices and restoring its leverage. The Saudis got the lower prices it was aiming for. It got bankruptcies it was hoping to induce as 81 American energy companies shuttered in the ensuing 18 months (see here for example just in 2016). It executed its strategy. But ultimately the Kingdom failed; its actions put a short-term blip on US oil production but couldn’t overcome the inherent efficiency and economics of shale and fracking.

Figure 4: US Oil Production (White) vs Oil Prices (Red)

Shale and fracking added 4 million barrels of supply to global markets. The 70% decline in crude oil in the second half of 2014 was only able to take 1 million barrels of production offline. From there, production surged an additional 50%, rising from over 8 million barrels per day to 13 million leading up to Covid. We saw a 50% surge in production in those ~5 years, all with oil prices nowhere close to the prior $100 level that markets saw before the 2014 crash. That’s why it seems doubtful that Saudi Arabia has shale in its sights now. Today, the oil industry is further consolidated, much better capitalized, and thus even further insulated from Saudi action. It’s far more likely that instead of global oil markets, Saudi Arabia’s messaging is directed towards maximizing production levels within OPEC, rather than energy markets globally.

3. Beta

In just about every profession students and young adults are exposed to certain concepts, principles, and ideas that never sniff applicability in the “real world.” It’s a natural and understandable occurrence; the academic “lab” is a place where ideas can be expressed in their most bare bones and theoretical manner without negative consequences. But the frustrating thing is that it can be a waste of time that could be spent on more productive and worthwhile topics.

In investing, the idea of an individual security’s “beta” fits the bill as one such topic. The idea of beta comes from the Capital Asset Pricing Model and thus has roots in the theory of efficient markets. The problem is it doesn’t hold to be true, at least according to Eugene Fama and Ken French – the very fathers of Efficient Market theory.

It doesn’t take much thought or investigation to see breakdowns in the idea of beta. Take the Financials sector. If you were a bank in the mid-2000s, in the biggest credit bubble ever, and in the largest sector at the time in the S&P 500, your beta was high. Today, it’s a lot lower. The same goes for energy where today the sector’s weight in the 500 is half of that pre-GFC. Beta has no regard for time horizon; the beta of a stock over 1 year is very different from 5 years and it’s worlds different from 10 years where compounding really bears fruit

In fact, if one believed in the Efficient Market Hypothesis you could calculate entirely different betas for the same stock, using the same expected return for the market and the same risk-free rate across time. Beta becomes just a plug-in; something derived to make the math of linear relationships in a larger system work for the sake of working.

Ultimately, beta does not tell you the why about a stock in any way shape, or form. It has no thoughts or insights into the capital allocation abilities of management or what multiple a business deserves. It cannot tell you what narrative is gripping the markets today or tomorrow. Today, anything with a semblance of an A.I. story gets rewarded. What was the beta to A.I. 4 years ago?

If you’re looking for beta you may as well just say you don’t want to own utilities and consumer staples stocks. But you don’t need to have any formal financial training to know that people’s consumption of soap does not accelerate in good times like airline tickets do.Sometimes a stock moves because the business reveals a new innovation, announces a merger, or appoints new management. Sometimes a stock will move because it is part of a larger market; it’s one fish in a giant pond and it can’t control the waves. That’s all. But instead, we have this compulsion to measure and compare what doesn’t matter.

4. Recommended Reads and Listens

Why Is It So Hard for China to Boost Domestic Demand

How to Revive Nuclear Power in the U.S.

Enterprise Philosophy and the First Wave of AI

New Zealand’s Building Boom – And What the World Must Learn From It