Emerging markets have grabbed a lot of our attention since 2008 and this priority of ours is considerably evident in our newsletters and commentaries since that time. It makes a great deal of sense for multiple reasons. First, many observers got a fresh reminder regarding the degree the globe, especially when it comes to banking and capital markets, is interconnected. Second, some major emerging market players (think China and Brazil) engaged in substantial stimulus measures as the links to demand from the developed world was limited. Finally, human nature in this day and age seems to always be looking forward whether it’s about the newest gadget we want or speculating on which country in the Middle East will revolt next, we seem to be creatures of large appetites and short memories.

Our narrative on the global economy and emerging markets should be clear by now to regular readers but we would like to discuss the topic of inflation as it is scaring some investors away from emerging markets.

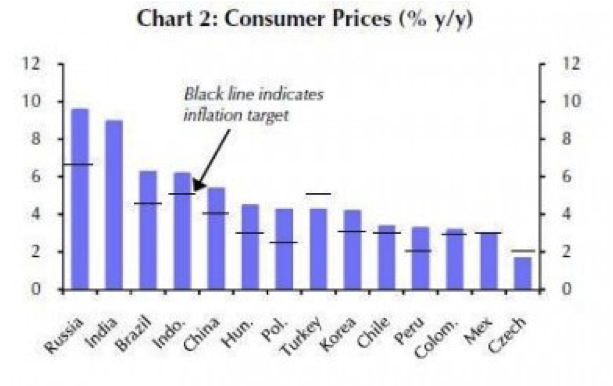

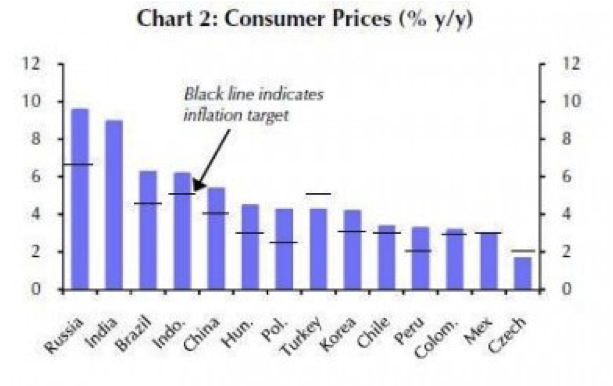

Figure 1: Emerging Markets Consumer Prices

Source: Stefan Wagstyl beyondbrics blog on Financial Times

The figure above details the rising price pressures in a wide range of emerging economies. Those who are skeptical of emerging markets point to these inflationary weights as a warning to get out before things boil over and asset values erode. Others say that the internal demand factors in emerging markets are robust enough to continue into the future. Joined with additional commodity pressures and secondary effects on wages, inflation will continue to be a hiccup in the emerging market growth story.

More than likely the reality lies in the middle regarding emerging market inflation. Is inflation – at least in food and energy – in these economies a certainty? Of course. But we need to ask why, and I think there are a couple of factors that get left out of the discussion a bit too often.

First, U.S. monetary policy has kept interest rates extremely low, limiting rates of return and increasing the appetite that investors would take their dollars and put them into emerging markets to capture a piece of the latter’s growth. The carry trade has riled up some finance ministers in the emerging world to speak of “currency wars” and employ capital controls of various kinds.

Second, demand from the West is still not at the level as before the crisis hit. Growth may remain below optimal levels. It may not get there any time soon as such enormous consumption appetites were inflated with credit and leverage. But without a more robust and stable recover of the American consumer, emerging markets will be hesitant to raise rates aggressively, choking off export competitiveness. Leaders in these countries are attempting to find that delicate balance of tightening simulative measures that many of their poor people still need while avoiding pricing goods outside the budget of their people. The fight is ongoing and aggressive in Brazil as traditional products of advantage, like ethanol, are actually losing ground to products from the U.S.

We believe demand from the West will recover eventually and zero interest rates can’t continue forever. The internal growth tools implanted in emerging economies have developed too much momentum for a harsh correction although we wouldn’t rule out bumps in the road. Just as we value precious metals for their finite quantity and tangibility we are still backing the emerging market growth machine due to its fundamentals of production and gradual realization of consumptive potential.

Ode to lift ups via advancing middle classes in emerging markets!

Inflation in Emerging Markets: Systemic Handicap or Short Term Concern

Author : John E. Charalambakis

Date : May 25, 2011

Emerging markets have grabbed a lot of our attention since 2008 and this priority of ours is considerably evident in our newsletters and commentaries since that time. It makes a great deal of sense for multiple reasons. First, many observers got a fresh reminder regarding the degree the globe, especially when it comes to banking and capital markets, is interconnected. Second, some major emerging market players (think China and Brazil) engaged in substantial stimulus measures as the links to demand from the developed world was limited. Finally, human nature in this day and age seems to always be looking forward whether it’s about the newest gadget we want or speculating on which country in the Middle East will revolt next, we seem to be creatures of large appetites and short memories.

Our narrative on the global economy and emerging markets should be clear by now to regular readers but we would like to discuss the topic of inflation as it is scaring some investors away from emerging markets.

Figure 1: Emerging Markets Consumer Prices

Source: Stefan Wagstyl beyondbrics blog on Financial Times

The figure above details the rising price pressures in a wide range of emerging economies. Those who are skeptical of emerging markets point to these inflationary weights as a warning to get out before things boil over and asset values erode. Others say that the internal demand factors in emerging markets are robust enough to continue into the future. Joined with additional commodity pressures and secondary effects on wages, inflation will continue to be a hiccup in the emerging market growth story.

More than likely the reality lies in the middle regarding emerging market inflation. Is inflation – at least in food and energy – in these economies a certainty? Of course. But we need to ask why, and I think there are a couple of factors that get left out of the discussion a bit too often.

First, U.S. monetary policy has kept interest rates extremely low, limiting rates of return and increasing the appetite that investors would take their dollars and put them into emerging markets to capture a piece of the latter’s growth. The carry trade has riled up some finance ministers in the emerging world to speak of “currency wars” and employ capital controls of various kinds.

Second, demand from the West is still not at the level as before the crisis hit. Growth may remain below optimal levels. It may not get there any time soon as such enormous consumption appetites were inflated with credit and leverage. But without a more robust and stable recover of the American consumer, emerging markets will be hesitant to raise rates aggressively, choking off export competitiveness. Leaders in these countries are attempting to find that delicate balance of tightening simulative measures that many of their poor people still need while avoiding pricing goods outside the budget of their people. The fight is ongoing and aggressive in Brazil as traditional products of advantage, like ethanol, are actually losing ground to products from the U.S.

We believe demand from the West will recover eventually and zero interest rates can’t continue forever. The internal growth tools implanted in emerging economies have developed too much momentum for a harsh correction although we wouldn’t rule out bumps in the road. Just as we value precious metals for their finite quantity and tangibility we are still backing the emerging market growth machine due to its fundamentals of production and gradual realization of consumptive potential.

Ode to lift ups via advancing middle classes in emerging markets!