It seems like these words have become part of every man, woman, and child’s lexicon in the midst of the Great Recession. With issues of debt and liabilities reaching sovereign proportions, economics as a subject is currently a witness to some fantastic debates about theory and policy; if it weren’t in the backdrop of financial calamity this would truly be a remarkable spectacle.

The conversation of sovereign debt has reached new heights as concerns range from small economies like Greece and Portugal, to large ones like the Eurozone as a whole, to even the United States. In the former economies, governments have opted for the austerity side of future policy (see Greece, Spain, and the UK for examples). A similar dilemma faces the United States, and given its role as the consumer of last resort, as well as home to the most liquid and trusted sovereign bond market, the spending/stimulus v. belt-tightening debate reaches new proportions. Yet the dollar’s rise – thanks to its safe-haven status – has postponed the deficit drama temporarily, but only at the federal level.

In the eye of the worst economic storm in 80 years, it’s disheartening to see so few news outlets and economists turn their attention to what’s brewing in states and municipalities across the U.S., specifically their bond markets. Like the federal government, and governments across the globe, states and municipalities ate out of the same pot of cheap credit and investment of toxic assets that has strangled countries, corporations, and banks. By issuing bonds at record levels (to finance investments whose returns aren’t generating enough cash to pay back debts) and making bets on interest-rate swaps in the billions, the financial crisis has rocked states and localities hard, bringing the debate on deficits to the forefront in these areas before federal adjustments will be made.

Outstanding municipal debt reached $2.8 trillion in June and state and local borrowing has reached 22% of U.S. GDP, an all time high. But what’s really grabbed our attention was an article published by Bloomberg stating that 46 states face a “Greek style crisis” with California (the globe’s 8th largest economy) and Illinois leading the charge. Since 2008 states have slashed budgets in public services such as education. This diminished spending raises unemployment and lowers prospective tax receipts, adding further pressure on growth and the ability for states to pay their debts.

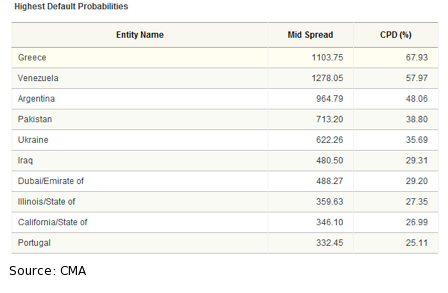

CMA, a well known agency for credit analysis, produced the following chart of global default probabilities, which is worth sharing.

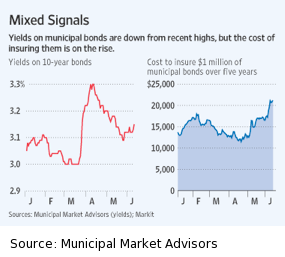

The idea of a state default seems unfathomable to most, especially one the size of California; some liken the crisis of the municipal bond market as another too big to fail sector of the financial industry. As a result, investors are snatching up municipal debt, seen in the following figure.

Optimists point to the chart on the left as a sign that municipal bonds will be OK as demand for debt is present while pessimists point to the graph on the right as an indicator of fear. So which is it?

Debt concerns at the state and federal level are tied together in terms of concerns for employment levels, tax revenues, and payments of debt; a problem at one level can inflict pain on the other and as we’ve written in our newsletters before, we see mountainous problems surfacing in the U.S. within the next decade, primarily in entitlement programs at the federal level. At the state level, pension obligations will pose severe budgetary hurdles in the same timeframe.

Investigations of several states and their pension obligations reveals that the state of Illinois will run out of funds to meet pension obligations by 2018, at current rates of return. Connecticut, Indiana, and New Jersey will follow the very next year and a total of 20 states could run out by 2025. Meeting obligations requires that states increase their annual obligations to pension funds by 75% over the next 10 years. At a time when belts are being tightened, public sector employees are being laid off, and growth prospects bleak, where this 75% will come from is an enormous question. Even if more funds are directed to pensions, the diverting of revenues lowers growth prospects and raises yield spreads on bonds, raising financing costs. Some estimates have found credit spreads to rise 10-20 basis points for every 10% of annual state revenue directed to pension fund obligations. The numbers could go up with further pressure on state budgets. Thus the drama that we expect to unfold with U.S. federal government could be played out at a micro level in the next few years if we turn out attention to the U.S. states.Of course the situation will be even more dramatic if things turn sour on a global scale in the next half of 2010 (see previous publications).

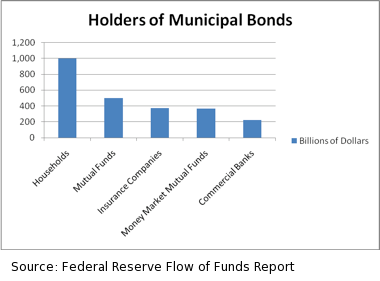

There are also short term considerations to remember with the municipal bond market. The number of insurers has dropped dramatically as insurance companies have been ravaged by the financial crisis. Thus, fewer investment grade municipal bonds remain as well as fewer insured bonds; of the $500 billion in municipal debt issued last year only 9% was insured by Forbes. Who’s most exposed to municipal bonds? Our next chart tells you.

As our website and newsletters have articulated, we don’t believe the U.S. economy, or the global economy for that matter is out of the woods. For the short term, it is entirely plausible to see a rise in the price for Treasury securities as uncertainty rises. This could harm the municipal bond market in the form of downward pressure on prices given its higher risk compared to U.S. government notes. Therefore, while it’s hard to argue against the long-term concerns in muncipal bonds, the short term could also spell harsh difficulties if investors demand higher returns, thus raising financing costs for states and local governments.

No matter which way is spun, and regardless of how little attention it receives, the municipal bond market and state budgets demonstrate the monumental hurdles that the American economy still has in front of it, both in the financial industry and the labor sector. Without either, growth and recovery will be multiple corners away.

It still promises to be an interesting ride!

A Prelude on Munis: The Drama of Debt, Deficits, Deflation, Entitlements, PIGS, & Austerity

Author : John E. Charalambakis

Date : July 12, 2010

It seems like these words have become part of every man, woman, and child’s lexicon in the midst of the Great Recession. With issues of debt and liabilities reaching sovereign proportions, economics as a subject is currently a witness to some fantastic debates about theory and policy; if it weren’t in the backdrop of financial calamity this would truly be a remarkable spectacle.

The conversation of sovereign debt has reached new heights as concerns range from small economies like Greece and Portugal, to large ones like the Eurozone as a whole, to even the United States. In the former economies, governments have opted for the austerity side of future policy (see Greece, Spain, and the UK for examples). A similar dilemma faces the United States, and given its role as the consumer of last resort, as well as home to the most liquid and trusted sovereign bond market, the spending/stimulus v. belt-tightening debate reaches new proportions. Yet the dollar’s rise – thanks to its safe-haven status – has postponed the deficit drama temporarily, but only at the federal level.

In the eye of the worst economic storm in 80 years, it’s disheartening to see so few news outlets and economists turn their attention to what’s brewing in states and municipalities across the U.S., specifically their bond markets. Like the federal government, and governments across the globe, states and municipalities ate out of the same pot of cheap credit and investment of toxic assets that has strangled countries, corporations, and banks. By issuing bonds at record levels (to finance investments whose returns aren’t generating enough cash to pay back debts) and making bets on interest-rate swaps in the billions, the financial crisis has rocked states and localities hard, bringing the debate on deficits to the forefront in these areas before federal adjustments will be made.

Outstanding municipal debt reached $2.8 trillion in June and state and local borrowing has reached 22% of U.S. GDP, an all time high. But what’s really grabbed our attention was an article published by Bloomberg stating that 46 states face a “Greek style crisis” with California (the globe’s 8th largest economy) and Illinois leading the charge. Since 2008 states have slashed budgets in public services such as education. This diminished spending raises unemployment and lowers prospective tax receipts, adding further pressure on growth and the ability for states to pay their debts.

CMA, a well known agency for credit analysis, produced the following chart of global default probabilities, which is worth sharing.

The idea of a state default seems unfathomable to most, especially one the size of California; some liken the crisis of the municipal bond market as another too big to fail sector of the financial industry. As a result, investors are snatching up municipal debt, seen in the following figure.

Optimists point to the chart on the left as a sign that municipal bonds will be OK as demand for debt is present while pessimists point to the graph on the right as an indicator of fear. So which is it?

Debt concerns at the state and federal level are tied together in terms of concerns for employment levels, tax revenues, and payments of debt; a problem at one level can inflict pain on the other and as we’ve written in our newsletters before, we see mountainous problems surfacing in the U.S. within the next decade, primarily in entitlement programs at the federal level. At the state level, pension obligations will pose severe budgetary hurdles in the same timeframe.

Investigations of several states and their pension obligations reveals that the state of Illinois will run out of funds to meet pension obligations by 2018, at current rates of return. Connecticut, Indiana, and New Jersey will follow the very next year and a total of 20 states could run out by 2025. Meeting obligations requires that states increase their annual obligations to pension funds by 75% over the next 10 years. At a time when belts are being tightened, public sector employees are being laid off, and growth prospects bleak, where this 75% will come from is an enormous question. Even if more funds are directed to pensions, the diverting of revenues lowers growth prospects and raises yield spreads on bonds, raising financing costs. Some estimates have found credit spreads to rise 10-20 basis points for every 10% of annual state revenue directed to pension fund obligations. The numbers could go up with further pressure on state budgets. Thus the drama that we expect to unfold with U.S. federal government could be played out at a micro level in the next few years if we turn out attention to the U.S. states.Of course the situation will be even more dramatic if things turn sour on a global scale in the next half of 2010 (see previous publications).

There are also short term considerations to remember with the municipal bond market. The number of insurers has dropped dramatically as insurance companies have been ravaged by the financial crisis. Thus, fewer investment grade municipal bonds remain as well as fewer insured bonds; of the $500 billion in municipal debt issued last year only 9% was insured by Forbes. Who’s most exposed to municipal bonds? Our next chart tells you.

As our website and newsletters have articulated, we don’t believe the U.S. economy, or the global economy for that matter is out of the woods. For the short term, it is entirely plausible to see a rise in the price for Treasury securities as uncertainty rises. This could harm the municipal bond market in the form of downward pressure on prices given its higher risk compared to U.S. government notes. Therefore, while it’s hard to argue against the long-term concerns in muncipal bonds, the short term could also spell harsh difficulties if investors demand higher returns, thus raising financing costs for states and local governments.

No matter which way is spun, and regardless of how little attention it receives, the municipal bond market and state budgets demonstrate the monumental hurdles that the American economy still has in front of it, both in the financial industry and the labor sector. Without either, growth and recovery will be multiple corners away.

It still promises to be an interesting ride!